- Arbitration

- Banking & Finance

- Capital Markets

- Commercial

- Competition

- Construction & Infrastructure

- Corporate / Mergers & Acquisitions

- Corporate Services

- Corporate Structuring

- Digital & Data

- Dispute Resolution

- Employment & Incentives

- Family Business & Private Wealth

- Innovation, Patents & Industrial Property (3IP)

- Insurance

Find a Lawyer

Book an appointment with us, or search the directory to find the right lawyer for you directly through the app.

Find out more

A Year-End Insight into Energy & Climate Law

This special edition of Law Update, marking Al Tamimi & Company’s 35th anniversary, explores the evolving legal landscape of energy and climate law across the region.

As the Middle East prioritises sustainable growth, this edition examines key developments shaping the future of the sector. From the UAE’s Federal Law No. 11 of 2024 to advancements in green hydrogen, solar financing, and carbon capture technology, we spotlight the innovative strides and challenges defining this critical area.

We also go into Saudi Arabia’s initiatives to integrate carbon capture into its industrial expansion and Egypt’s AFRICARBONEX platform, which underscores the region’s commitment to a sustainable and inclusive future.

Join us as we celebrate 35 years of legal excellence and forward-thinking insights, paving the way for a more sustainable tomorrow.

Read Now

The leading law firm in the Middle East & North Africa region.

A complete spectrum of legal services across jurisdictions in the Middle East & North Africa.

-

Practices

- All Practices

- Banking & Finance

- Capital Markets

- Commercial

- Competition

- Construction & Infrastructure

- Corporate / Mergers & Acquisitions

- Corporate Services

- Corporate Structuring

-

Sectors

-

Country Groups

-

Client Solutions

Today's news and tomorrow's trends from around the region.

17 offices across the Middle East & North Africa.

Our Services

Back

Back

-

Practices

- All Practices

- Banking & Finance

- Capital Markets

- Commercial

- Competition

- Construction & Infrastructure

- Corporate / Mergers & Acquisitions

- Corporate Services

- Corporate Structuring

- Digital & Data

- Dispute Resolution

- Employment & Incentives

- Family Business & Private Wealth

- Innovation, Patents & Industrial Property (3IP)

- Insurance

- Intellectual Property

- Legislative Drafting

- Private Client Services

- Private Equity

- Private Notary

- Projects

- Real Estate

- Regulatory

- Tax

- Turnaround, Restructuring & Insolvency

- White Collar Crime & Investigations

-

Sectors

-

Country Groups

-

Client Solutions

- Law Firm

- /

- Insights

- /

- Law Update

- /

- November 2018

- /

- A Finger on the Pulse of Middle East Healthcare

A Finger on the Pulse of Middle East Healthcare

Andrea Tithecott - Partner, Head of Regulatory and Healthcare - Commercial / Regulatory / Legislative Drafting / Sustainability focused Corporate Governance / Sustainable Finance / Sustainable Business / Sustainable Sourcing / Climate Change & Energy Transition / Projects

As the pressure increases on Middle Eastern countries’ governments to control and reduce public spending on healthcare services, the door is firmly open to the private sector to invest on a bigger scale than ever before. In this article, we examine the economic and political imperatives of attracting inward private sector healthcare investment and look at what Middle Eastern governments are doing to make the ‘whole package’ more appealing in terms of a stable environment in which to do business as well as a solid regulatory framework that will govern health facilities and practitioners.

“In the UAE, the emirates of Abu Dhabi and Dubai are moving towards a ‘certificate of need’ requiring the investor to do their due diligence, understand what services are required and look at how they can fulfil that need.”

Sector growth

One of the key questions for investors is whether there are opportunities for further growth. Market forecast reports and sector analysts have reported forecasted growth year-on-year, with the statistics for 2018 suggesting the GCC member states, alone, will see healthcare expenditure of somewhere in the range of US $104.6 billion by 2022. Within this overall forecast we see considerable variation, and in some cases, uncertainty.

In the UAE, forecasts are also driven by local factors, inevitably, the recovery in oil prices, but also the expected success of Expo 2020. In the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (‘KSA’), again, oil price plays a significant part, but is linked to the potential listing of a small percentage of Saudi Aramco that will be used to build the investment fund, which will fuel many of the healthcare projects identified in the KSA’s Transformation Plan 2030. The healthcare sector has been allocated 15 per cent of the KSA’s total 2018 budgeted expenditures, increasing to SAR 147 million from actual spend of SAR 133 million during 2017. This 10.5 per cent increase in the budget allocation is an indicator of potential growth and the opportunities for the private sector in the KSA’s healthcare market.

Meanwhile, the political situation as between some of the GCC member states and the State of Qatar has caused growth to slow as international investors have less confidence in the GCC being a cohesive unit and a place where a regional investment strategy can be successful.

Health insurance

If the public purse is firmly closed something has to replace it. This year has witnessed a continued roll out of either new health insurance regulations (such as in the Kingdom of Bahrain) or added components to existing regulation (such as in the UAE). The GCC member states are keen to have mandated health insurance for both their respective local population and expatiate workforce. Equally, each of the member states is keen to avoid the USA’s model of insurance, which has seen the costs of healthcare spiral. In the UAE, the reimbursement rates for medical services will be firmly controlled. This is currently the case in the Emirate of Abu Dhabi (Abu Dhabi Law No. 23 of 2005, concerning Health Insurance), with the Emirate of Dubai soon to follow suit with their recent law (Local Law No. 8 of 2018) that will regulate prices of medical services offered by private healthcare facilities.

Insurance regulators and payors in each of the GCC member states will need to carefully examine what services will be capable of reimbursement, and how those payment models are going to work. We see this as moving away from a ‘fee for service’ model to a ‘fee for value’ model that will help keep costs under control. If health facilities and payors can find a way forward on such an alternative model, it opens the door to more affordable health services through preventative medicine, setting quality outcome targets, telemedicine, and the use of technology and innovative techniques to deliver services more efficiently. Going one step further, if there can be an alignment of fees on a regional basis, it further incentivises international investors to look at regional projects rather than country specific projects.

Public Private Partnership

A core pillar of the transformation of healthcare services for the Middle East will be the opportunities for public private partnerships (‘PPP’).

The GCC member state Kuwait is no stranger to PPP projects. Many of Kuwait’s major water and power projects and healthcare projects (including, the Kuwait Health Assurance Company, Hospital for Expatriates and the Jaber Al Ahmad Jaber Al Sabah Hospital, being awarded to an Arab consortium) were intended to be delivered on a PPP basis (Kuwait Law No. 116 of 2014 concerning Public Private Partnerships).

More recently, the UAE and the KSA have concluded that PPP is the best route to securing private sector investment for largerscale projects. The Dubai Health Authority (‘DHA’), has begun to discuss how to promote the introduction of more PPP projects into the healthcare system (Dubai Law No. 22 of 2015, governing Public Private Partnerships). The DHA is creating an investment strategy that will ‘promote Dubai as a viable and competitive hub for investment in healthcare that addresses the needs of the Emirate and the future opportunities, and provides the best service for investors and enable sustainable public-private model in Dubai’ (DHA Investment Strategy 2017–2020). The first Dubai PPP healthcare projects are expected to be put out to tender soon, in parallel with a Dubai PPP healthcare regulation, and will include a significant new project to develop a cardiac centre of excellence.

The KSA has recently published its own draft PPP law, consulting with the private healthcare sector and seeking comments on what the sector wants from such a law. The success of many of the projects outlined in the KSA’s Vision 2030 will depend on the KSA implementing an attractive PPP law, in parallel with foreign investors being able to own 100 per cent of a health facility, which is an initiative expected to provide a much needed commercial incentive to the private sector to commit to investment opportunities in KSA’s healthcare.

Master capacity plans and medical tourism

Whether a regulator is creating a health services’ plan for its local population, or with a view to expanding into medical tourism, having a detailed plan as to what services are needed is fundamental to enable a government to deliver on its obligation to provide services, and to then monitor and supervise the delivery of services, quality, and price.

In the UAE, the Emirates of Abu Dhabi and Dubai are moving towards a ‘certificate of need’ requiring the investor to do its due diligence, understand what services are required, and look at how it can fulfil that need. This applies not only to traditional core services but also to new specialist services that are currently not offered. One example, being the new stem cell regeneration facility within the Jumeirah Hospital in Dubai, the first such facility to be granted a licence in the UAE.

An investor wishing to bring new innovative treatments and services can access helpful advice and guidance from the DHA by completing a simple form to explain their ‘offering’ and obtaining a quick preliminary view as to whether a licence is likely to be granted, without having to spend time and money on an expensive facility application.

A new medical city called NEOM City which is to be located on the Red Sea coast will provide a boost to medical tourists from Egypt and Jordan, as well as from the KSA, for ‘lifestyle’ and wellness services. This mirrors the Dubai Healthcare City phase 2 programme, which is focused on wellness and prevention. Bahrain has announced a plan to develop the Dilmunia Health District. Abu Dhabi’s ruler has announced a virtual medical city for Abu Dhabi, and Oman plans to construct an international medical city. It is expected that the services provided in such medical cities will need to be innovative, using new technology platforms, wearable monitoring devices, and artificial intelligence to deliver personalised medicine and improved clinical outcomes.

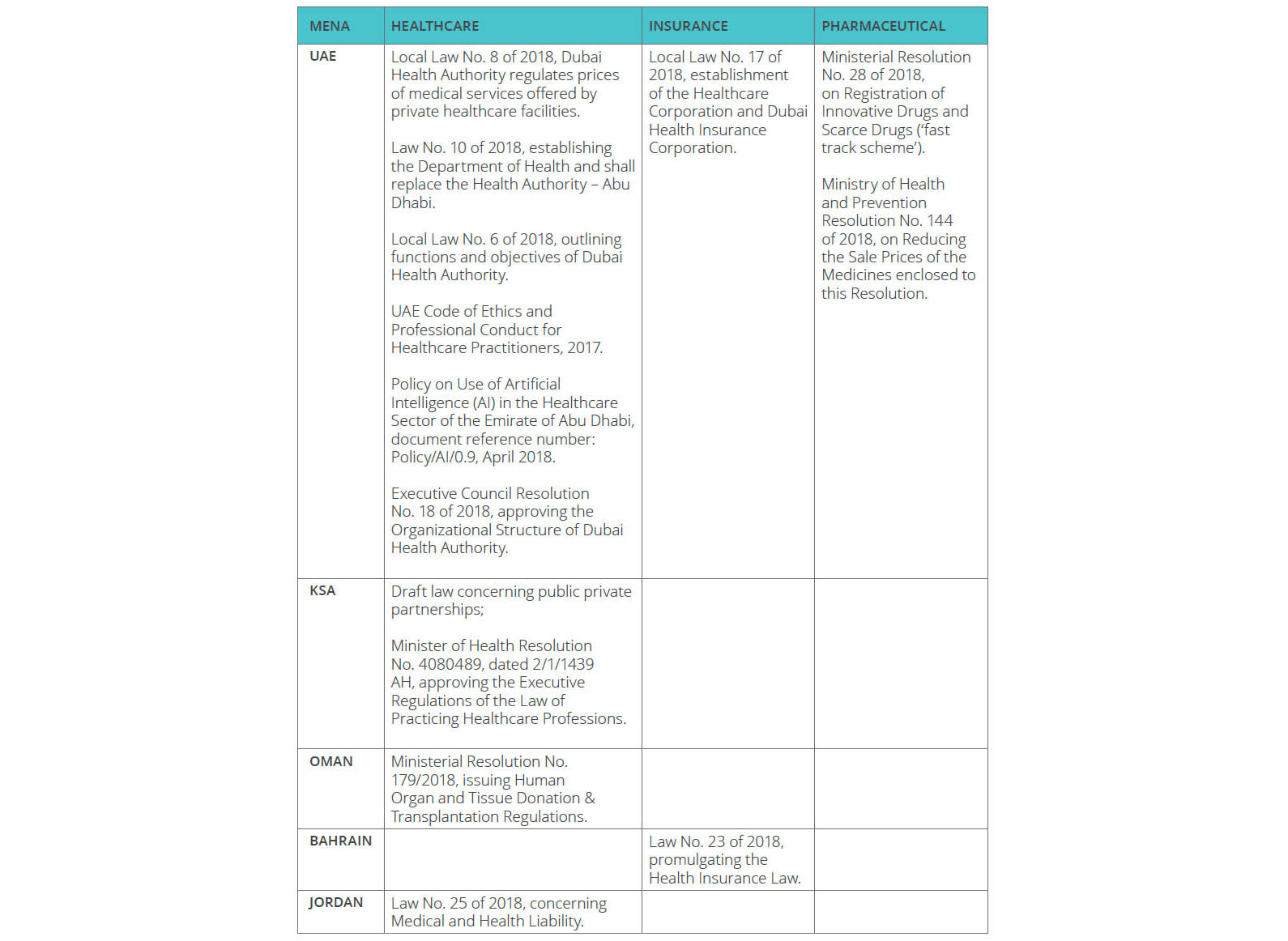

Healthcare regulation update

In 2018, we have seen a marked increase in the delivery of new regulation governing healthcare and life sciences. The examples given in the table are just the tip of the iceberg. Alongside primary law, sits a vast amount of regulatory codes of practice, guidance, and procedural documents to support the ever increasing range of activities that need to be formally licensed and approved by the regulators.

Conclusion

Across the Middle East region there are a multitude of healthcare sector initiatives underway. In future Law Update articles, we will cover other government announcements, progress on projects, such as PPP, and the development of centres of excellence in order that the private healthcare sector can invest in and support more complex medical needs and be able to offer those services and boosting medical tourism.

Al Tamimi & Company’s Healthcare team regularly advises on all matters pertaining to healthcare and life sciences matters. For further information please contact Andrea Tithecott (a.tithecott@tamimi.com).

Stay updated

To learn more about our services and get the latest legal insights from across the Middle East and North Africa region, click on the link below.