- Arbitration

- Banking & Finance

- Capital Markets

- Commercial

- Competition

- Construction & Infrastructure

- Corporate / Mergers & Acquisitions

- Corporate Services

- Corporate Structuring

- Digital & Data

- Dispute Resolution

- Employment & Incentives

- Family Business & Private Wealth

- Innovation, Patents & Industrial Property (3IP)

- Insurance

Find a Lawyer

Book an appointment with us, or search the directory to find the right lawyer for you directly through the app.

Find out more

The Technology Issue

Decoding the future of law

This Technology Issue explores how digital transformation is reshaping legal frameworks across the region. From AI and data governance to IP, cybersecurity, and sector-specific innovation, our lawyers examine the fast-evolving regulatory landscape and its impact on businesses today.

Introduced by David Yates, Partner and Head of Technology, this edition offers concise insights to help you navigate an increasingly digital era.

2025 is set to be a game-changer for the MENA region, with legal and regulatory shifts from 2024 continuing to reshape its economic landscape. Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Egypt, Iraq, Qatar, and Bahrain are all implementing groundbreaking reforms in sustainable financing, investment laws, labor regulations, and dispute resolution. As the region positions itself for deeper global integration, businesses must adapt to a rapidly evolving legal environment.

Our Eyes on 2025 publication provides essential insights and practical guidance on the key legal updates shaping the year ahead—equipping you with the knowledge to stay ahead in this dynamic market.

The leading law firm in the Middle East & North Africa region.

A complete spectrum of legal services across jurisdictions in the Middle East & North Africa.

-

Practices

- All Practices

- Banking & Finance

- Capital Markets

- Commercial

- Competition

- Construction & Infrastructure

- Corporate / Mergers & Acquisitions

- Corporate Services

- Corporate Structuring

-

Sectors

-

Country Groups

-

Client Solutions

Today's news and tomorrow's trends from around the region.

17 offices across the Middle East & North Africa.

Our Services

Back

Back

-

Practices

- All Practices

- Banking & Finance

- Capital Markets

- Commercial

- Competition

- Construction & Infrastructure

- Corporate / Mergers & Acquisitions

- Corporate Services

- Corporate Structuring

- Digital & Data

- Dispute Resolution

- Employment & Incentives

- Family Business & Private Wealth

- Innovation, Patents & Industrial Property (3IP)

- Insurance

- Intellectual Property

- Legislative Drafting

- Private Client Services

- Private Equity

- Private Notary

- Projects

- Real Estate

- Regulatory

- Tax

- Turnaround, Restructuring & Insolvency

- Compliance, Investigations and White-Collar Crime

-

Sectors

-

Country Groups

-

Client Solutions

- Law Firm

- /

- Insights

- /

- Law Update

- /

- November 2019

- /

- Dispelling the Taboo: Kuwait’s First Mental Health Law

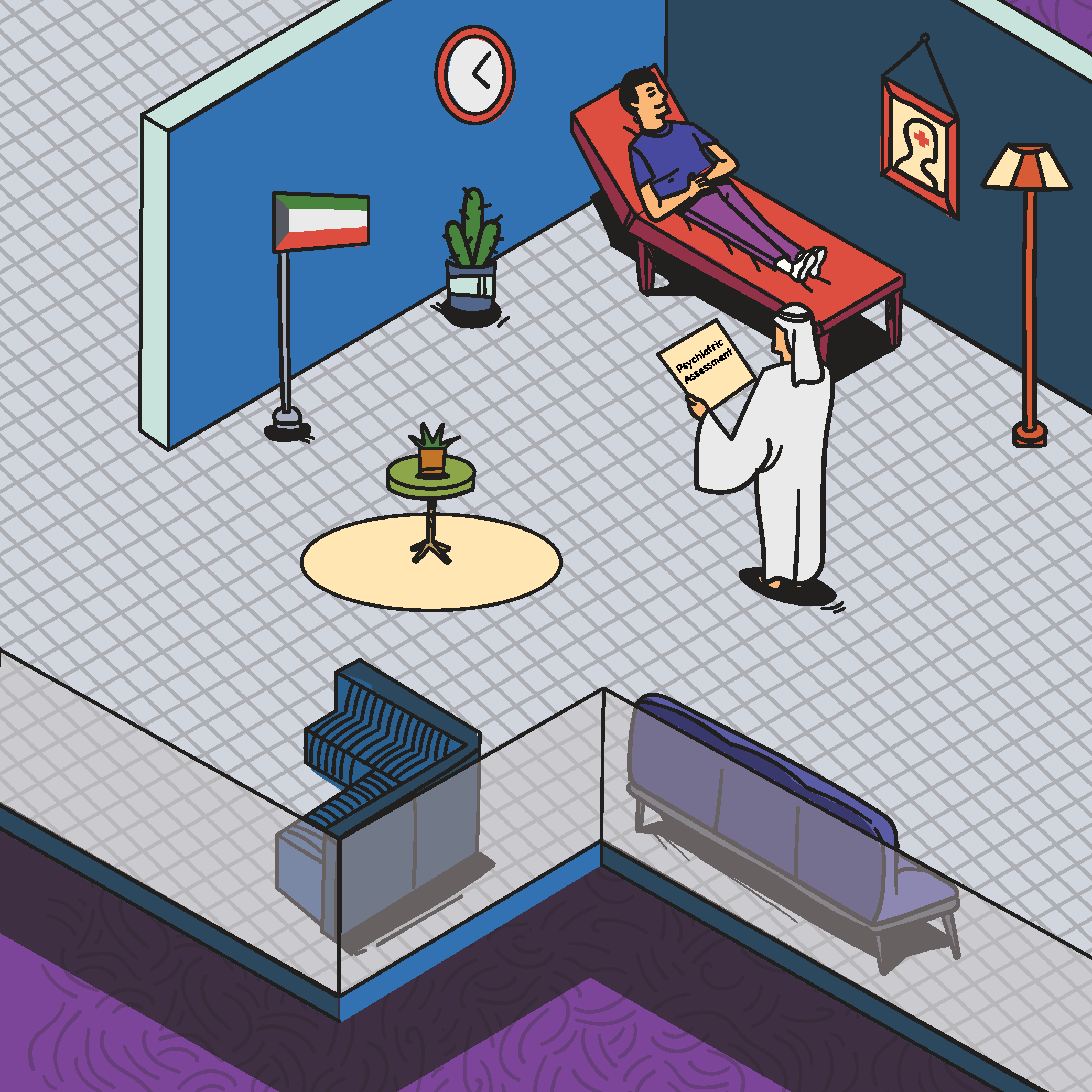

Dispelling the Taboo: Kuwait’s First Mental Health Law

Margaret McKenzie

In February 2019, the Kuwait Government issued Law No. 14 of 2019 (‘Mental Health Law’). The law endeavours to protect individuals with mental health issues. Prior to this law, there was no law governing mental health in Kuwait. Although the legislation cannot, on its own, decrease the prevalence of mental illness or the stigma surrounding mental health in Kuwaiti society, it remains a promising step towards change.

In February 2019, the Kuwait Government issued Law No. 14 of 2019 (‘Mental Health Law’). The law endeavours to protect individuals with mental health issues. Prior to this law, there was no law governing mental health in Kuwait. Although the legislation cannot, on its own, decrease the prevalence of mental illness or the stigma surrounding mental health in Kuwaiti society, it remains a promising step towards change.

The Mental Health Law addresses enhancing mental health treatment and combating mental illness. The Mental Health Law defines mental health as “the state of well-being in which every individual realises his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to her or his community.” The law further defines mental illness as “the state of psychological or mental disorder resulting from the impairment of any psychological or mental function to the extent that limits the individual adaptation to his or her social environment. It does not include the use or addiction to alcohol, drugs, psychotropic substances, or medications without apparent mental illness.”

The law includes the creation of the Mental Health Coordinating Council (‘MHCC’), which comprises 11 members who are empowered to follow up on the application of the law and its executive regulations, including developing policies in respect of the rights of mental health patients, amongst others. The MHCC is also tasked with creating the Monitoring and Evaluation Committee, which comprises a consultant, an experienced psychiatric therapist, and a legal consultant working in the legal sector of Ministry of Health. This committee has the purview to deliver independent medical reports about a patient’s case that has been referred to it, receive complaints, change a patient’s status from compulsory to voluntary admission in a mental health facility, consider the validity of compulsory admission and treatment procedures being applied, consider the patient’s ability to make treatment decisions, consider the continued detention of patients under judicial orders, and any other further functions assigned.The law addresses requirements and procedures for the psychiatric assessment of mental health patients, voluntary and compulsory admission to psychiatric units or facilities, and compulsory mental health treatment. Prior to the issuance of the Mental Health Law, an individual facing mental issues could not be detained at a facility, even if leaving the facility would likely result in harm to himself or others. Article 11 of the Mental Health Law affords a physician the right to prevent a patient from leaving a facility for up to 72 hours while undergoing evaluation (‘Assessment Period’), if, on the basis of a psychiatric assessment, the physician deems that the patient could cause imminent harm to himself or others, or that the patient, due to mental illness, is unable to take care of himself/herself or to consent to voluntary assessment or treatment. Following the Assessment Period, the patient may be voluntarily or compulsorily admitted for treatment in a mental health facility.

Further, if there is a judicial order, a person may be referred without his or her consent for a psychiatric assessment. A patient may also be transferred without consent if reasonably requested by any of the following: (i) a relative of the patient, up to second kinship; (ii) a treating physician or therapist in mental health; or (iii) one of the investigators of the General Directorate of Investigation. If there is no longer a reason for compulsory admission, a therapist may cancel the Assessment Period at any time and authorise the patient to be discharged. Following the psychiatric assessment, the patient may be voluntarily or compulsorily admitted for treatment in a mental health facility.

However, it is worth noting that no person can be compulsorily admitted to a mental health facility unless a psychiatrist, who is not the same as the referrer for compulsory assessment, prepares a new psychiatric assessment, when there are clear signs of severe mental illness. The law explains that severe mental illness includes the following: (i) severe and imminent deterioration of mental or health condition because of symptoms of mental illness; or (ii) where mental illness signifies a serious and imminent threat to the safety, health, or life of the patient or others.

An exception to these compulsory admission procedures includes emergency and urgent cases. Under such cases, a patient may be compulsorily admitted and examined so long as a preliminary diagnosis report and rationale for emergency admission is submitted to the facility management and Monitoring and Evaluation Committee within 24 hours of the examination, and within 48 hours of examination to the Public Prosecution to take necessary action.

Should the patient have the capacity to understand and provide informed consent to treatment, then his consent should be obtained prior to the administration of any treatment. If the guardian of a mental patient who is incapable of making a treatment decision refuses treatment, or if there is no guardian representative, the Monitoring and Evaluation Committee must approve treatment until the court appoints a guardian.

In addition to the procedures surrounding the admission of an individual, the Mental Health Law sets forth punishments under Articles 30-34. Namely, the pro-patient law imposes stringent punishment if there is any violation of the law. Violations include, but are not limited to, financial and criminal sanctions. If a person intentionally admits a person who is suffering from mental illness to a place or under conditions other than those prescribed by law, there is a penalty of imprisonment between one to three years and a fine of 3,000 to 10,000 Kuwaiti Dinars (approx. US$10,000 – 33,000). Further, if a person enables or assists a person who is subject to compulsory treatment to escape or falsely informs a competent authority about a person who suffers from mental illness, then he or she will be subject to imprisonment for one to three years and a fine of 1,000 to 5,000 Kuwaiti Dinars (approx. US$3,000 – 16,000). Additionally, a person who discloses a patient’s psychological secrets may be imprisoned for a period of three months to two years and fined 1,000 to 5,000 Kuwaiti Dinars (approx. US$3,000 – 16,000).

The law not only focuses on mental health treatment, but encourages patient rehabilitation as well. The law states that the Ministry of Health will establish shelters for patients who do not need to stay at a mental health facility and whose families refuse to provide appropriate care. Further, the law permits the Ministry of Health to grant private shelter licences for these purposes.

The law also highlights that a person treated in a mental health facility or who has a mental health condition should not be precluded from obtaining a job with a government entity. By encouraging employment of individuals with mental health conditions, the law intends to further prevent stigma and isolation for mental health patients.

The first of its kind in Kuwait, the Mental Health Law highlights the government’s continuous effort to improve patient protections in a region where mental illness remains taboo. The law implements strict penalties for individuals who violate the law, as it dedicates five articles out of 40 clearly listing the consequences of violating the law. Although still in its early stages, the Mental Health Law indicates an important step in improving healthcare development as well as the rights and treatment of mental health patients and communities in Kuwait.

Al Tamimi & Company’s Healthcare Practice in Kuwait regularly advises on laws and regulations impacting the healthcare sector. For further information please contact healthcare@tamimi.com.

Stay updated

To learn more about our services and get the latest legal insights from across the Middle East and North Africa region, click on the link below.