- Arbitration

- Banking & Finance

- Capital Markets

- Commercial

- Competition

- Construction & Infrastructure

- Corporate / Mergers & Acquisitions

- Corporate Services

- Corporate Structuring

- Digital & Data

- Dispute Resolution

- Employment & Incentives

- Family Business & Private Wealth

- Innovation, Patents & Industrial Property (3IP)

- Insurance

Find a Lawyer

Book an appointment with us, or search the directory to find the right lawyer for you directly through the app.

Find out more

The Technology Issue

Decoding the future of law

This Technology Issue explores how digital transformation is reshaping legal frameworks across the region. From AI and data governance to IP, cybersecurity, and sector-specific innovation, our lawyers examine the fast-evolving regulatory landscape and its impact on businesses today.

Introduced by David Yates, Partner and Head of Technology, this edition offers concise insights to help you navigate an increasingly digital era.

2025 is set to be a game-changer for the MENA region, with legal and regulatory shifts from 2024 continuing to reshape its economic landscape. Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Egypt, Iraq, Qatar, and Bahrain are all implementing groundbreaking reforms in sustainable financing, investment laws, labor regulations, and dispute resolution. As the region positions itself for deeper global integration, businesses must adapt to a rapidly evolving legal environment.

Our Eyes on 2025 publication provides essential insights and practical guidance on the key legal updates shaping the year ahead—equipping you with the knowledge to stay ahead in this dynamic market.

The leading law firm in the Middle East & North Africa region.

A complete spectrum of legal services across jurisdictions in the Middle East & North Africa.

-

Practices

- All Practices

- Banking & Finance

- Capital Markets

- Commercial

- Competition

- Construction & Infrastructure

- Corporate / Mergers & Acquisitions

- Corporate Services

- Corporate Structuring

-

Sectors

-

Country Groups

-

Client Solutions

Today's news and tomorrow's trends from around the region.

17 offices across the Middle East & North Africa.

Our Services

Back

Back

-

Practices

- All Practices

- Banking & Finance

- Capital Markets

- Commercial

- Competition

- Construction & Infrastructure

- Corporate / Mergers & Acquisitions

- Corporate Services

- Corporate Structuring

- Digital & Data

- Dispute Resolution

- Employment & Incentives

- Family Business & Private Wealth

- Innovation, Patents & Industrial Property (3IP)

- Insurance

- Intellectual Property

- Legislative Drafting

- Private Client Services

- Private Equity

- Private Notary

- Projects

- Real Estate

- Regulatory

- Tax

- Turnaround, Restructuring & Insolvency

- Compliance, Investigations & International Cooperation

-

Sectors

-

Country Groups

-

Client Solutions

- Law Firm

- /

- Insights

- /

- Law Update

- /

- November 2019

- /

- Impact of Nationalisation Policies in the UAE and KSA Healthcare Sector

Impact of Nationalisation Policies in the UAE and KSA Healthcare Sector

Mohsin Khan - Partner - Employment and Incentives

Sabrina Saxena - Partner - Employment and Incentives

Introduction

Introduction

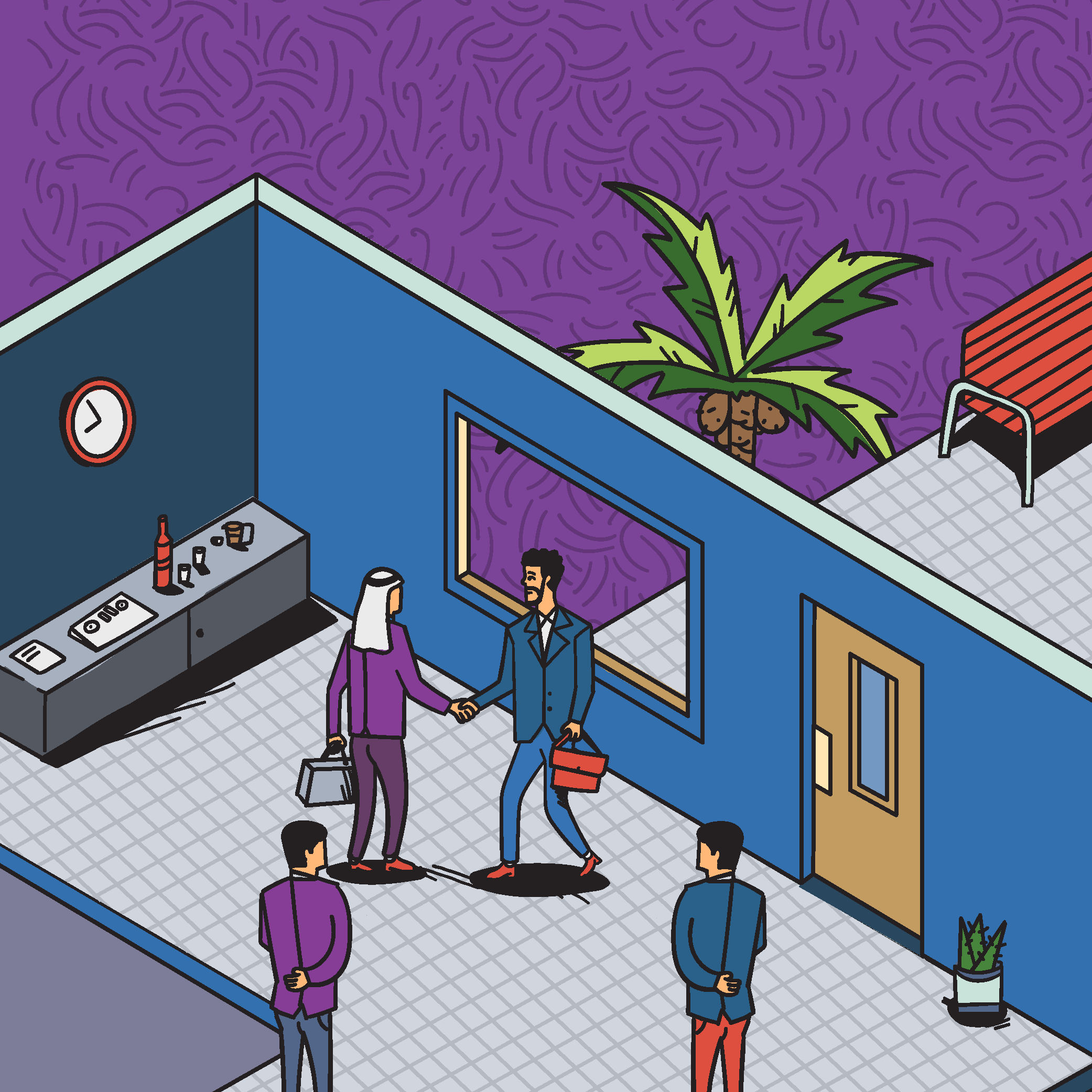

Both the United Arab Emirates (‘UAE’) and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (‘KSA’) pursue policies of nationalisation in order to create employment opportunities for local nationals. In this article, we look at how each country is implementing its nationalisation policies and how those policies are impacting the healthcare sector.

UAE

On Sunday 29 September 2019, it was announced following a cabinet meeting, that over 20,000 job opportunities would be created for UAE nationals in a variety of sectors across the UAE. The Cabinet also approved an AED 300 million (US$81,744) fund to train approximately 18,000 Emirati jobseekers. These announcements are part of the UAE’s ongoing push towards Emiratisation, that is, the employment of Emiratis within the UAE workforce.

Whilst the UAE Labour Law does make provision for the priority of UAE nationals over other nationalities when employers are recruiting in the UAE, historically, this has not been enforced in practice save in certain industries and for pre-determined job titles within larger companies. Healthcare companies were not previously subject to Emiratisation requirements or quotas (unlike banks and insurance companies).

Recently, the Ministry of Human Resources and Emiratisation (‘MOHRE’) introduced two separate pilot projects to encourage the recruitment of UAE nationals in the private sector, which do not distinguish between company size or sector and thereby encompass the healthcare sector. These include:

- Tawteen Gate; and

- pre-determined job title restrictions.

These new projects are currently being implemented in onshore entities only, and there is no express Emiratisation requirement in free zone entities, although free zone entities are being encouraged to act in the ‘spirit’ of Emiratisation.

Tawteen Gate

Under the Tawteen Gate system, upon the submission of a new work permit for an expatriate through the regular MOHRE process, MOHRE will review the application and determine whether there is an UAE national registered with Tawteen as a job seeker (‘Emirati Candidate’), looking for a similar title. The Tawteen process is triggered automatically upon the submission of a work permit application.

If there is Emirati Candidate in the market for a job with the job title requested, the MOHRE will put the current expatriate work permit application on hold and send the company the CV of eligible Emirati Candidate(s) for review.

The company will then be required to review these CV(s). The Emirati Candidate will also be provided with an opportunity to consider the role and determine whether or not he/she wishes to accept the position.

If the company does not consider the Emirati Candidate(s) to be suitable for the role, it will need to provide a sufficient reason(s) as to why the application will not be progressed. For example, the Emirati Candidate does not have the appropriate qualifications or experience for the advertised position.

MOHRE may also request the company to attend an ‘Open Day’ to meet with the Emirati Candidate(s). To emphasise, if the company does not wish to hire an Emirati Candidate(s), it will need to provide justifiable reasons as to why.

If there are no Emirati Candidates who are suitable for the role, the company may proceed with its expatriate work permit application.

Job Title Restrictions

Under this system, approximately 1,500 job titles have been classified as 1 – 5, with category 1 being the most desirable and best remunerated. Job titles classified under categories 1 and 2 are generally linked to the more senior or more qualified positions including (but not limited to) chemists, general practitioners, specialised physicians (including surgeons, cardiologists, paediatricians etc.), nurses, and laboratory technicians. These roles, amongst others, are now predominantly set aside for Emiratis in the first instance, and a company will be pro-actively blocked from hiring expatriates into these positions.

Not all companies are currently subject to this restriction and, in the case of those which are not: (i) the authorities will contact the company directly when the restriction should apply to it; or (ii) the company will only become aware of the restriction once it makes an application for a new expatriate work permit and the preferred job title is not available.

In such circumstances, a company representative will be required to approach a Tawteen Happiness Centre, and the authorities will then suggest prospective and appropriate UAE national candidates who are available. If there is no UAE national available for the role, the company may hire an expatriate. If there is an UAE national looking for a similar role, the company will be required to review the CV and potentially meet with the candidate. If the company does not wish to hire the individual, it will need to provide reasons for not hiring the individual and only once this process has been satisfied, may it go on to hire an expatriate.

During this recruitment process, the company’s establishment card will be blocked. Ultimately, this process will cause some delay in the hiring process and companies should therefore factor this process into the hiring process timeline.

KSA

The concept of Saudisation has been in place for decades. Indeed, the Saudi Labour Law, issued by Royal Decree Number M/51 dated 23 Sha’ban 1426 (corresponding to 27, September 2005), as amended from time to time (the ‘KSA Labour’) Law, stipulates that at least 75 percent of an employer’s total workforce must be Saudi nationals. However, in practice, Saudisation was not strictly implemented until the Ministry of Labour (‘MoL’) introduced the Nitaqat programme in 2013. The Nitaqat programme operates by classifying employers into six categories – Platinum, Green (High, Medium and Low), Yellow and Red – depending on various factors such as the size and activity of the company as well as the percentage of Saudi nationals in the workforce compared to expatriate employees. In general, an employer benefits from being in a higher category through greater incentives, such as flexibility in recruiting and managing expatriate employees, lower processing fees, and other administrative benefits. By contrast, lower graded entities will have restricted immigration and sponsorship benefits. Accordingly, under the current iteration of the Nitaqat programme, an employer’s ability to recruit foreign nationals is subject to its level of compliance with its Saudisation requirements. Companies that are compliant are likely to be able to apply for visas for foreign nationals, whereas companies that are non-compliant are restricted from applying for visas for foreign nationals.

In addition to being compliant with Saudisation requirements, companies must first apply for a work permit from the MoL in order to recruit a foreign national. The MoL has a wide discretionary authority to grant work permits and will only do so if there is an insufficient number of suitably qualified Saudi nationals available to perform the role for which a company is seeking to recruit a foreign national. Previously, there was also a requirement to advertise a vacancy on the Human Resources Development Fund’s online national jobs portal (Taqat) before they could recruit foreign nationals to fill that vacancy, although this requirement was removed in November 2018.

Furthermore, the MoL and, in some cases, other competent authorities such as the Saudi Food and Drug Authority, have also directed that specific sectors or professions be subject to complete Saudisation such that the roles available in those sectors or professions are reserved only for Saudi nationals.

In this context, and as part of the Vision 2030 programme to diversify the KSA economy away from its dependence on oil, it is anticipated that over 171,000 jobs in the healthcare sector will be held by Saudi nationals by 2027, up from the current level of approximately 75,000. Some roles have already been subject to complete Saudisation. For example, certain roles, including medical representatives and pharmacovigilance roles, must be undertaken by licensed pharmacists who can only be Saudi nationals. Similarly, the role of sales representatives of medical equipment or devices has been reserved exclusively for Saudi nationals as of January 2019. It is expected that other roles within the healthcare sector will also be reserved for Saudi nationals only. Even where roles may not be fully reserved for Saudi nationals only, it is likely that there will be an increase in the proportion of Saudi nationals taking up roles within the healthcare sector in the near future, as the Saudi authorities are keen to increase employment opportunities for the increasing number of Saudi graduates who are entering the labour market. Saudisation rates are expected to be particularly high in the professions of dentists and pharmacists. This is likely to result in a reduction in the number of foreign nationals within the KSA healthcare sector as Saudi nationals accumulate experience resulting in the healthcare sector becoming less reliant on foreign nationals. It also means that it will become more difficult to recruit foreign nationals into KSA as the MoL is less likely to grant work permits if there are a suitable number of Saudi nationals available to undertake a variety of roles within the healthcare sector.

Conclusion

Both the UAE and the KSA are making a noticeable push towards the employment of national locals, aiming to promote their contribution to the economy as well as development-oriented policies that support productive activities and enhanced job creation. This, therefore, directly impacts the healthcare sector, in respect of both large and small organisations. Along with the emphasis on job creation, the UAE has proposed a national programme of awareness among citizens, job seekers, students, schools, higher education institutions and parents about the value of work and the advantages offered by the private sector.

In conclusion, therefore, whilst nationalisation policies are a positive initiative that will boost growth in both the UAE and the KSA in the long-term, companies should be aware of the additional obligations being enforced, in order to effectively manage their operational requirements.

Al Tamimi & Company’s Healthcare Practice includes lawyers from our Employment & Incentives team who regularly advise on laws and regulations impacting the healthcare sector. For further information, please contact healthcare@tamimi.com.

Stay updated

To learn more about our services and get the latest legal insights from across the Middle East and North Africa region, click on the link below.