- Arbitration

- Banking & Finance

- Capital Markets

- Commercial

- Competition

- Construction & Infrastructure

- Corporate / Mergers & Acquisitions

- Corporate Services

- Corporate Structuring

- Digital & Data

- Dispute Resolution

- Employment & Incentives

- Family Business & Private Wealth

- Innovation, Patents & Industrial Property (3IP)

- Insurance

Find a Lawyer

Book an appointment with us, or search the directory to find the right lawyer for you directly through the app.

Find out more

Real Estate & Construction and Hotels & Leisure

Real estate, construction, and hospitality are at the forefront of transformation across the Middle East – reshaping cities, driving investment, and demanding increasingly sophisticated legal frameworks.

In the June edition of Law Update, we take a closer look at the legal shifts influencing the sector – from Dubai’s new Real Estate Investment Funds Law and major reforms in Qatar, to Bahrain’s push toward digitalisation in property and timeshare regulation. We also explore practical issues around strata, zoning, joint ventures, and hotel management agreements that are critical to navigating today’s market.

As the landscape becomes more complex, understanding the legal dynamics behind these developments is key to making informed, strategic decisions.

2025 is set to be a game-changer for the MENA region, with legal and regulatory shifts from 2024 continuing to reshape its economic landscape. Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Egypt, Iraq, Qatar, and Bahrain are all implementing groundbreaking reforms in sustainable financing, investment laws, labor regulations, and dispute resolution. As the region positions itself for deeper global integration, businesses must adapt to a rapidly evolving legal environment.

Our Eyes on 2025 publication provides essential insights and practical guidance on the key legal updates shaping the year ahead—equipping you with the knowledge to stay ahead in this dynamic market.

The leading law firm in the Middle East & North Africa region.

A complete spectrum of legal services across jurisdictions in the Middle East & North Africa.

-

Practices

- All Practices

- Banking & Finance

- Capital Markets

- Commercial

- Competition

- Construction & Infrastructure

- Corporate / Mergers & Acquisitions

- Corporate Services

- Corporate Structuring

-

Sectors

-

Country Groups

-

Client Solutions

Today's news and tomorrow's trends from around the region.

17 offices across the Middle East & North Africa.

Our Services

Back

Back

-

Practices

- All Practices

- Banking & Finance

- Capital Markets

- Commercial

- Competition

- Construction & Infrastructure

- Corporate / Mergers & Acquisitions

- Corporate Services

- Corporate Structuring

- Digital & Data

- Dispute Resolution

- Employment & Incentives

- Family Business & Private Wealth

- Innovation, Patents & Industrial Property (3IP)

- Insurance

- Intellectual Property

- Legislative Drafting

- Private Client Services

- Private Equity

- Private Notary

- Projects

- Real Estate

- Regulatory

- Tax

- Turnaround, Restructuring & Insolvency

- Compliance, Investigations and White-Collar Crime

-

Sectors

-

Country Groups

-

Client Solutions

- Law Firm

- /

- Insights

- /

- Law Update

- /

- April 2020

- /

- Law in the time of COVID-19: force majeure under DIFC law

Law in the time of COVID-19: force majeure under DIFC law

Rita Jaballah - Partner, Head of International Litigation - International Litigation Group / Litigation / Family Business / Turnaround, Restructuring and Insolvency / Sustainability focused Corporate Governance / Sustainable Finance / Sustainable Business / Sustainable Sourcing / Climate Change & Energy Transition

![]() The widespread effects of the COVID-19 pandemic have had a serious impact on the ability of commercial parties to honour the terms of their contracts in the DIFC, Dubai and beyond.

The widespread effects of the COVID-19 pandemic have had a serious impact on the ability of commercial parties to honour the terms of their contracts in the DIFC, Dubai and beyond.

Necessary government public health measures have forced the closure of many companies, from nurseries and schools to retail malls, cinemas and gyms, and restricted the operation of many more, with consequences across the payment and supply chains.

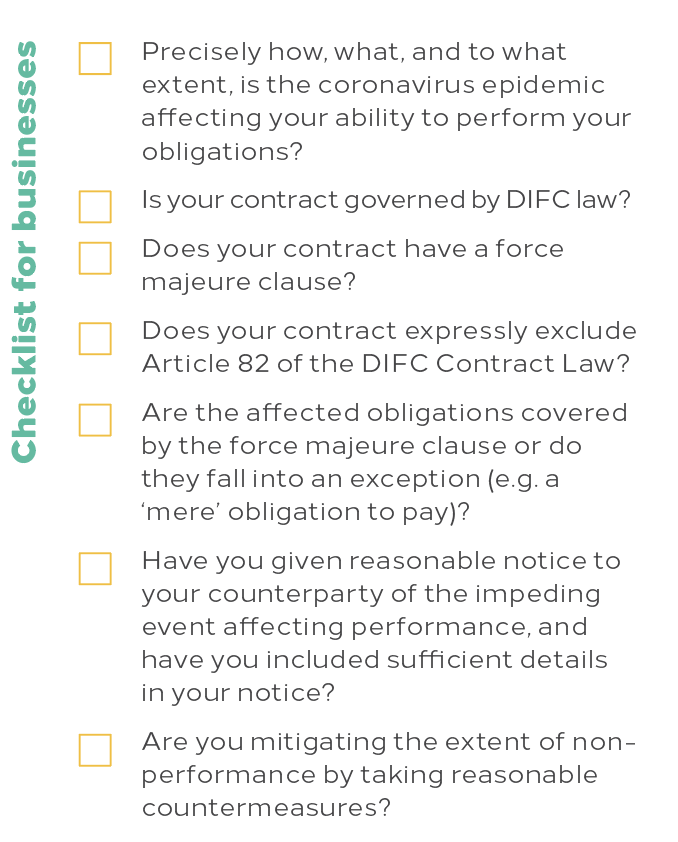

Many businesses are checking the terms of their agreements to see what provisions cover the disruption caused by the COVID-19. This article considers how contracts governed by DIFC law may respond in this crisis.

Force majeure in commercial contracts

A force majeure clause is engaged by the occurrence of a specified event or events, which can occur with or without human intervention. Broadly, there are two requirements in order for an event to constitute force majeure:

- the event cannot have reasonably been foreseen by the parties; and

- the event was completely beyond the parties’ control and they could not have prevented its consequences.

Many contracts will contain explicit force majeure terms, particularly business-to-business agreements and those drafted by experienced lawyers.

The precise operation of the clause will depend on its wording. Typically, the risks covered are identified and listed and, in the case of COVID-19, in the first instance parties should look for wording covering the risks of “epidemic”, “pandemic”. “quarantine” or “notifiable diseases”.

Parties should also bear in mind that the responsive measures taken by the authorities in the UAE or elsewhere may also be circumstances of force majeure, such as ‘any law or any action taken by a government or public authority’. In addition, non-performance by third party entities such as suppliers or subcontractors may also be covered.

Some clauses may also contain ‘catch-all’ provisions intended to cover all other events ‘beyond the reasonable control of the parties’, which would tend to include the COVID-19 outbreak.

Once triggered, a force majeure clause usually permits one or more parties to agree to take one or more of the following actions, in whole or in part:

- cancel the contract;

- provide a lawful excuse from performance;

- seek the suspension of performance; or

- stipulate an extension of time for performance.

Force majeure under DIFC Law

Force majeure under DIFC Law

In English law, if the contract does not contain an express force majeure clause, no term is likely to be implied to the same effect. The position is different for contracts governed by DIFC law as the DIFC Contract Law (DIFC Law No.6 of 2004) effectively implies a force majeure term into DIFC law governed contracts at Article 82(1):

‘Except with respect to a mere obligation to pay, non-performance by a party is excused if that party proves that the non-performance was due to an impediment beyond its control and that it could not reasonably be expected to have taken the impediment into account at the time of the conclusion of the contract or to have avoided or overcome it or its consequences.’

Article 82(1) follows the requirements of force majeure clauses listed above: the force majeure event is not reasonably foreseen and is beyond the parties’ control. The key exception to this clause is in respect of an obligation to pay.

This means that in a contract such as a lease governed by DIFC law, Article 82(1) alone will not excuse a tenant from payment of rent due if it cannot make payment due to the COVID-19.

Article 82(1) and its implication is very important in relationships like those between employers and employees, where express force majeure clauses are rare. Note, however, that parties can vary or exclude Article 82 in their agreement (Article 11, DIFC Contract Law).

The effect of force majeure

Article 82(2) stipulates that, when the impediment is only temporary, the excuse shall have effect for such period as is reasonable having regard to the effect of the impediment on performance of the contract. The COVID-19 epidemic is likely only to be temporary, which means it is unlikely (but not impossible, depending on the commercial circumstances) that the affected party could justifiably seek the cancellation of the contract by relying on Article 82.

A ‘reasonable’ period of reliance on force majeure will depend on a number of factors including the commercial purpose and practical operation of the contract, its subject matter and the connection between the coronavirus and the affected party’s impediment.

Notice requirements

Article 83(3) sets out notice requirements: notice must be given by the affected party to its counterparty, with an explanation of its ability to perform, within a reasonable period of time after the affected party knew or ought to have known of the impediment. A failure to give notice in a reasonable time will make the affected party liable for damages. Article 13(1) of the DIFC Court Law provides that notice may be given ‘by any means appropriate to the circumstances’ unless the agreement stipulates otherwise).

The precise operation of a contractual force majeure clause will depend on its wording but usually the clause should:

- contain a notification provision, setting out a period within which the affected party should notify the other party (usually in writing) of the event of force majeure, giving basic details of the event such as the date on which it started, its duration and the effect of the event on the affected party’s ability to perform any of its obligations under the agreement; and

- oblige the affected party to use all reasonable endeavours to mitigate the effect of the event on the performance of its obligations.

The consequence of a validly notified force majeure may also be stipulated, in such a way that states the affected party is not in breach of the agreement and extending the time for performance.

Proper notification is very important. In several cases brought by property owners against a developer in respect of delays to the construction and hand-over of apartments in a DIFC development caused by third party contractors, the Courts considered the validity of the notices of force majeure served by the defendant which purported to exercise its right to extend the anticipated completion date. The judge at first instance had found that the notices issued had failed to satisfy the requirements of the contractual force majeure clause: neither the force majeure event nor the extent of delay of the impeding event had been identified, with a substantial effect on the delay analysis and, amongst others, entitling the claimants to damages ((1) Kenneth David Rohan (2) Andrew James Mostyn Pugh (3) Michelle Gemma Mostyn Pugh (4) Stuart James Cox v Daman Real Estate Capital Partners Limited and Ahmed Zaki Beydoun & (1) Daman Real Estate Capital Partners Limited (2) Asteco Property Management LLC [2013] DIFC CA 005 and CA 006, 16 October 2014).

Other contractual and statutory rights

Article 82(4) explicitly recognises that nothing in the Article prevents a party from exercising a right to terminate the contract or to withhold performance or request interest on money due. Those actions, of course, will been considered lawful or unlawful in light of DIFC law and a proper construction of the relevant rights themselves. Article 86 of the DIFC Contract Law permits termination where the failure of the other party to perform an obligation under the contract amounts to a fundamental non-performance, the ascertainment of which will have regard to a number of factors including whether the non-performance substantially deprives the aggrieved party of what it was entitled to expect under the contract and whether it has reason to believe it cannot rely on the other party’s future performance.

The treatment of force majeure by the DIFC Courts

As well as the Daman cases above, the DIFC Courts have considered force majeure cases on several other occasions.

In Gert v Germaine [2016] DIFC SCT 097, the defendant landlord was unable to rely on force majeure for a failure to carry out maintenance to cure the smell of sewage in the property leased by the claimant tenant when the landlord was unable, through no fault of his own, to access the property for maintenance. In DIFC Investments LLC v Mohammed Akbar Mohammed Zia [2017] DIFC CFI 001 the Court of First Instance confirmed that Article 82 applied to contracts governed by DIFC law without the requirement for an express term.

Whilst these cases are each confined to their specific facts, parties should note that in none of the cases was the defendant able to rely successfully and in full on the force majeure terms. Affected parties should bear in mind that the scope of the clause, exceptions to its coverage (such as mere obligations to pay), and notification requirements may all shape the extent to which a term can be relied on to excuse non-performance.

Generally speaking, common law precedents, and particularly English case law, are persuasive in the DIFC. In future cases, relevant cases may shape issues like the interpretation of the force majeure clause, the burden of proof, and requirements of the clause’s invocation including that a force majeure event is the only effective cause of default by a party under a contract relying on a force majeure provision.

Frustration of the contract

As a common law court, the DIFC Courts are able to supplement DIFC law with the application of the common law, including the doctrine of frustration, as DIFC law makes no specific provision for frustration in the DIFC Contract Law or elsewhere in its statutes.

The doctrine usually requires the performance of the contract to be impossible, not ‘merely’ very difficult, time-consuming or expensive to perform. The doctrine may excuse both parties from their obligations if contractual performance becomes impossible, whether physically or legally, thereby frustrating the contract. Generally, the doctrine requires a higher threshold than force majeure.

Litigating in the time of COVID-19: the reduced operation of the DIFC Courts

If disputes arise in respect of insufficient or non-performance of contractual obligations, businesses should check what dispute resolution terms apply.

If a dispute falls into the exclusive civil and commercial jurisdiction of the DIFC Courts, whether because of the parties involved in the dispute or its subject matter, or because the parties have opted into the DIFC Courts’ jurisdiction, for the most part parties should not experience any disruption or delays in connection with filing claims or responses and the listing of hearings.

Parties should be aware, however, of the DIFC Courts’ restricted work practices, as announced on its website (at www.difccourts.ae/2020/03/17/covid-19-difc-courts-update/ and subject to change). The principal changes at as of 23 March 2020 are:

- from 17 March until 26 April 2020 or further notice, the DIFC Courts will be physically closed and all staff will work remotely;

- all hearings in the Courts (whether CFI or SCT) will be by teleconference or videoconference;

- parties are urged to use the e-bundling platform, particularly given the additional difficulties of hard copy bundling in an environment of ‘social distancing’ and severed physical communications.

Parties should plan accordingly, particularly if urgent applications or interim relief are sought.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic is unique in modern times and underscores the extent of globalisation and our interconnected world from a human and economic perspective. Of course other pandemics have swept the world before, and will do so in the future. These facts do not reduce the costs of the disease, the numbers of lives lost or the economic disruption caused. But, as the wording of Article 82 reminds us, the interruption will ultimately only be temporary.

For further information, please contact Peter Smith (p.smith@tamimi.com), Peter Wood (p.wood@tamimi.com) or Rita Jaballah (r.jaballah@tamimi.com).

Stay updated

To learn more about our services and get the latest legal insights from across the Middle East and North Africa region, click on the link below.