- Arbitration

- Banking & Finance

- Capital Markets

- Commercial

- Competition

- Construction & Infrastructure

- Corporate / Mergers & Acquisitions

- Corporate Services

- Corporate Structuring

- Digital & Data

- Dispute Resolution

- Employment & Incentives

- Family Business & Private Wealth

- Innovation, Patents & Industrial Property (3IP)

- Insurance

Find a Lawyer

Book an appointment with us, or search the directory to find the right lawyer for you directly through the app.

Find out more

Game Theory

2025 is set to be a game-changer for the MENA region, with legal and regulatory shifts from 2024 continuing to reshape its economic landscape. Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Egypt, Iraq, Qatar, and Bahrain are all implementing groundbreaking reforms in sustainable financing, investment laws, labor regulations, and dispute resolution. As the region positions itself for deeper global integration, businesses must adapt to a rapidly evolving legal environment.

Our Eyes on 2025 publication provides essential insights and practical guidance on the key legal updates shaping the year ahead—equipping you with the knowledge to stay ahead in this dynamic market.

The leading law firm in the Middle East & North Africa region.

A complete spectrum of legal services across jurisdictions in the Middle East & North Africa.

-

Practices

- All Practices

- Banking & Finance

- Capital Markets

- Commercial

- Competition

- Construction & Infrastructure

- Corporate / Mergers & Acquisitions

- Corporate Services

- Corporate Structuring

-

Sectors

-

Country Groups

-

Client Solutions

Today's news and tomorrow's trends from around the region.

17 offices across the Middle East & North Africa.

Our Services

Back

Back

-

Practices

- All Practices

- Banking & Finance

- Capital Markets

- Commercial

- Competition

- Construction & Infrastructure

- Corporate / Mergers & Acquisitions

- Corporate Services

- Corporate Structuring

- Digital & Data

- Dispute Resolution

- Employment & Incentives

- Family Business & Private Wealth

- Innovation, Patents & Industrial Property (3IP)

- Insurance

- Intellectual Property

- Legislative Drafting

- Private Client Services

- Private Equity

- Private Notary

- Projects

- Real Estate

- Regulatory

- Tax

- Turnaround, Restructuring & Insolvency

- White Collar Crime & Investigations

-

Sectors

-

Country Groups

-

Client Solutions

- Law Firm

- /

- Insights

- /

- Law Update

- /

- Venture Capital & Emerging Companies Law Review

- /

- Polls: Insights from the Region’s Leading VC Funds and Angel Investors

Polls: Insights from the Region’s Leading VC Funds and Angel Investors

Abdullah Mutawi - Partner, Head of Corporate Commercial - Corporate / Mergers and Acquisitions / Commercial / Private Equity / Digital & Data / Turnaround, Restructuring and Insolvency / Venture Capital and Emerging Companies

In collaboration with Middle East Venture Capital Association (MEVCA).

Polling angel investors and venture capitalists in the MENA region: testimonies of a growing ecosystem

In the wake of more and more regional success stories, the venture capital asset class has certainly taken on a life of its own over the past two years. The more traditional later stage private equity, once the regional go-to asset class of alternative investments, is losing ground for numerous reasons both obvious and not-so-obvious. Venture capital is attracting sovereign wealth funds, institutions, individuals, and family enterprises. In the family office category, there is a clear pattern of third-generation family members taking charge of diversifying into venture, and fund managers chasing big returns.

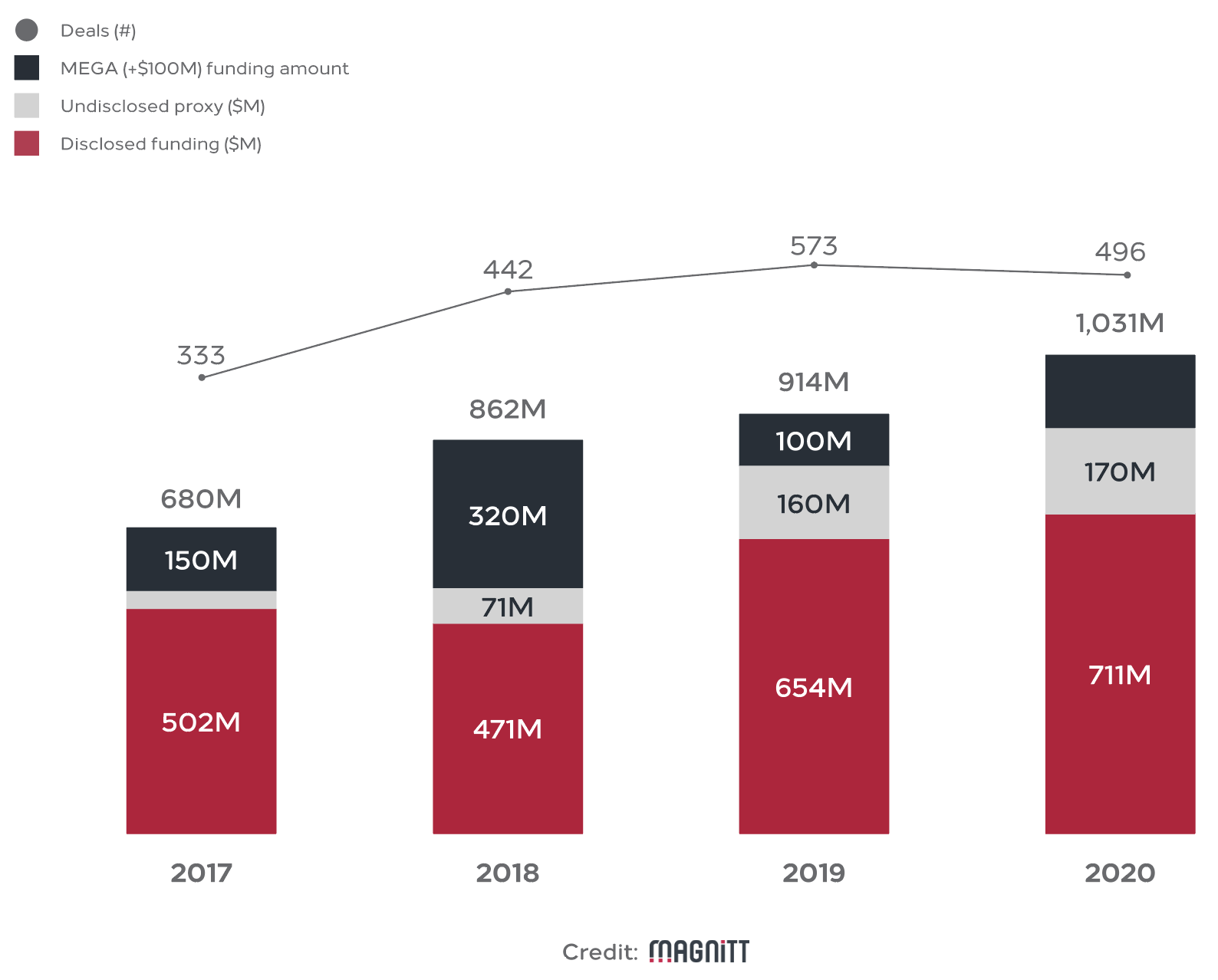

The growth of the MENA venture capital investments

Mid to late-stage private equity will typically see investors looking for controlling stakes, with cheques starting at the USD 10 to 50 million mark. In venture capital, cheques are much smaller, especially in the earlier stages of start-ups, and co-investments are the norm rather than the exception. Moreover, venture investors will avoid taking a controlling stake in a company, with contractual arrangements between shareholders dictating the governance obligations. Venture capital comes at a time when companies are at the early-stage of their development, and there needs to be room for future investors to participate in the upside.

Venture capital investors will write a much larger number of cheques with the same amount of capital as a PE investor, providing relatively stronger portfolio diversification. This is extremely important as the risk profile of companies is much higher, with both the potential rewards and probability of failure being very high. Contrarily to later stage private equity, venture investors cannot rely on financial fundamentals. Even with second and third-time founders, companies are often pre-revenue, and investors are looking at other factors to determine the strength of the opportunities.

Out of an abundance of curiosity and a desire to present some meaningful data, we have conducted two very similar surveys of both venture capital funds and active individual angel investors to find out their deciding factors when considering an opportunity. Angel investors are often successful entrepreneurs and professionals working in the entrepreneurial space, and are writing smaller cheques at an earlier stage than venture funds. They provide value through their investment and their advice, having been through the motions of growing a company, or having domain expertise and insight that can be applied by the start-up. Venture funds will typically come in after angel investors in companies looking to develop their vision or proof of concept and have a slightly different framework of analysis than angel investors.

Frameworks of analysis

Please rank each of the following in terms of importance in your investment decisions

We can see from the results that angel investors and venture investors apply a similar framework of analysis. Quality of the team is the most important factor. As a matter of fact, not a single responder did not say that it was critical. At this stage, founders have the vision, plan, and drive to build the company. An early stage company is only as good as its founders.

For angel investors, the next most important things are the business model, go-to-market strategy, and product-market fit. This is a telltale sign that angels are investing early. They want to see that the founders have a path to product market fit and growth. The focus on business model and go-to-market strategy are a way to gauge the vision of the founder, which needs to be grounded in reality. Acquiring first customers is hard, and the necessary first step for product-market fit. Some start-ups will have product-market fit at this stage and be in hypergrowth, but most will only need to demonstrate a believable path to achieving product-market fit through customer acquisition strategies.

For venture investors, product-market fit is the clear second after the team, with less focus on go-to-market strategy and business model. In most cases, venture investors will help grow the company following initial demonstrable results. Product-market fit is proof that there is a strong addressable market, as well as the fact that the start-up found a way to address the issue being tackled. Venture investors will not look twice at a company that built a fantastic product if its potential customers are not interested in using it.

Another point of divergence in the groups is that moats and traction are keys for the venture investors, while comparatively less important for angel investors. This is a reflection of the different phases of an early-stage company. Angel investors will invest in the team and the vision, and it will be the founders’ responsibility to build a unique product and add sufficient value to it in order stay a pioneer. When venture investors come in, they will need to make sure that the start-up has defenses against the risk of being copied, and that they are making their name in their market. Traction will demonstrate growth potential and moats will demonstrate survival potential. Both of those are necessary.

Valuation is important for both groups, and so is the fact that the start-up has more than one founder. The fact that those factors are flipped for each group is a strong indicator of their differences. On the one hand, angels will be more willing to back a solo founder if they can identify with them and the valuation is right. They will have a stronger focus on price as the risk profile of the company is at the highest. On the other hand, venture investors will be more flexible on price if it means getting to back a promising company. However, they will want to see that there is a team that can keep up with the growth. It is very difficult for solo founders to stay on top of fast-growing companies and in most cases, solo founders will only be considered if they are repeat entrepreneurs with a proven track of success.

Being at the inception of the company’s history, long-term considerations are less important. Exit opportunities are still far away and the company will go through drastic changes. It is important that the investors believe that there is a path to exit, but less so that this path is defined.

Finally, board seats and governance matters are at the bottom for both groups. This is because in the early stages, before Series A, governance will often be handled informally. Investors will provide advice to founders and the company is still small enough that there is no need for formal processes. However, we must note that even though it came last for both groups, it was still reported as far more important for venture investors than it was for angels. This reflects the fact that venture investors come in at a turning point for start-ups: their evolution from vision to adoption.

Considerations on company profile

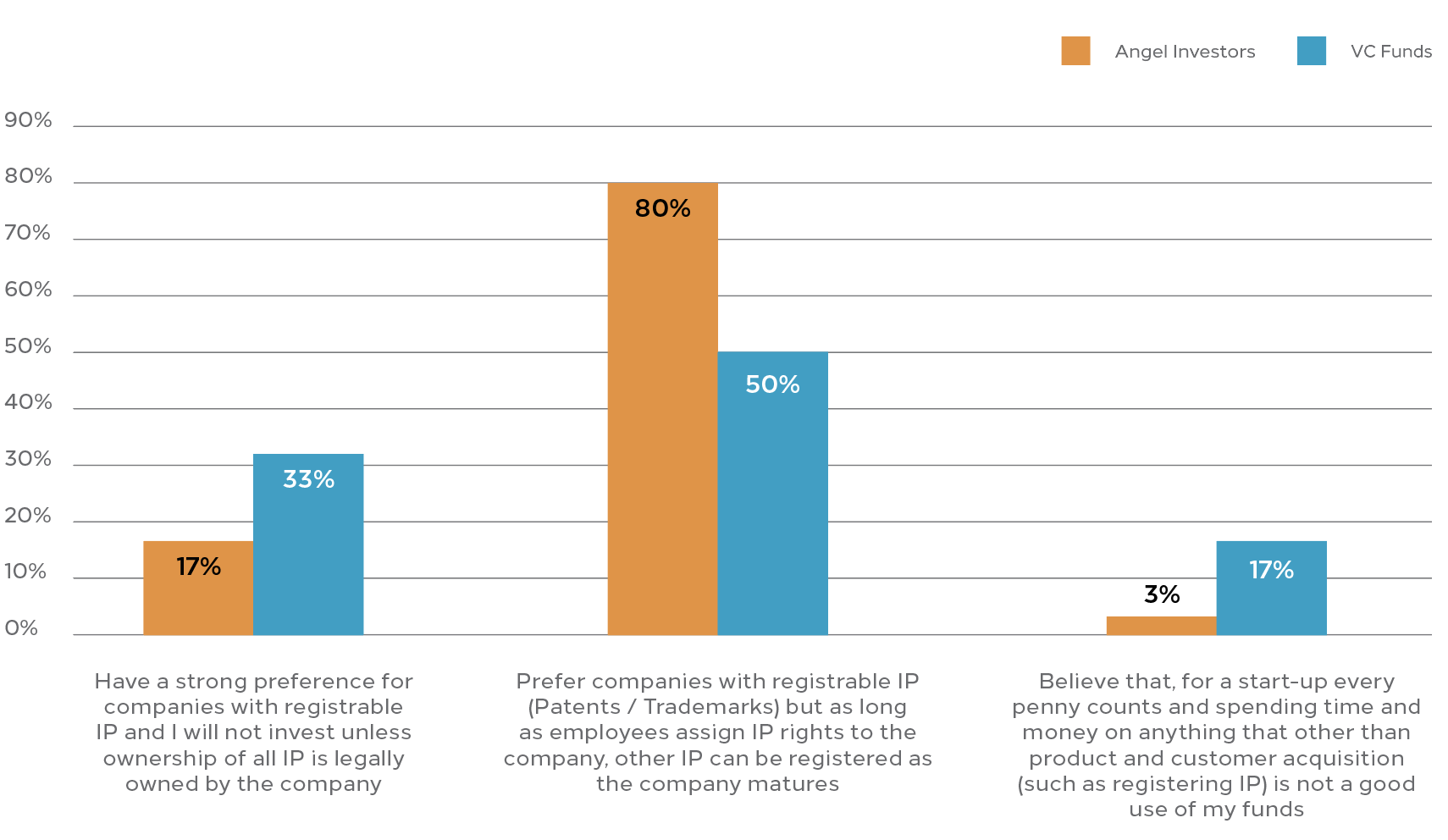

There are two topics we wanted to analyze in further detail: intellectual property and employee incentive plans.

Start-ups are often built on their intellectual property. Deep tech start-ups will be highly valued thanks to their patents, digital native brands will hold value in their trademarks and logos, and companies built on operational excellence will need to protect their trade secrets. While trade secrets are not registerable, trademarks and logos are and can be expensive. Patents are a whole other level and can make start-ups fundraise for the sole purpose of being able to afford the registration. We asked investors their position on registerable IP:

Intellectual Property

Both groups find it important, with angels allowing companies more leeway. Once again, this is because angels typically invest earlier, and will accept to fund less structured companies. Venture investors will typically make their funding conditional on the registration of the relevant intellectual property.

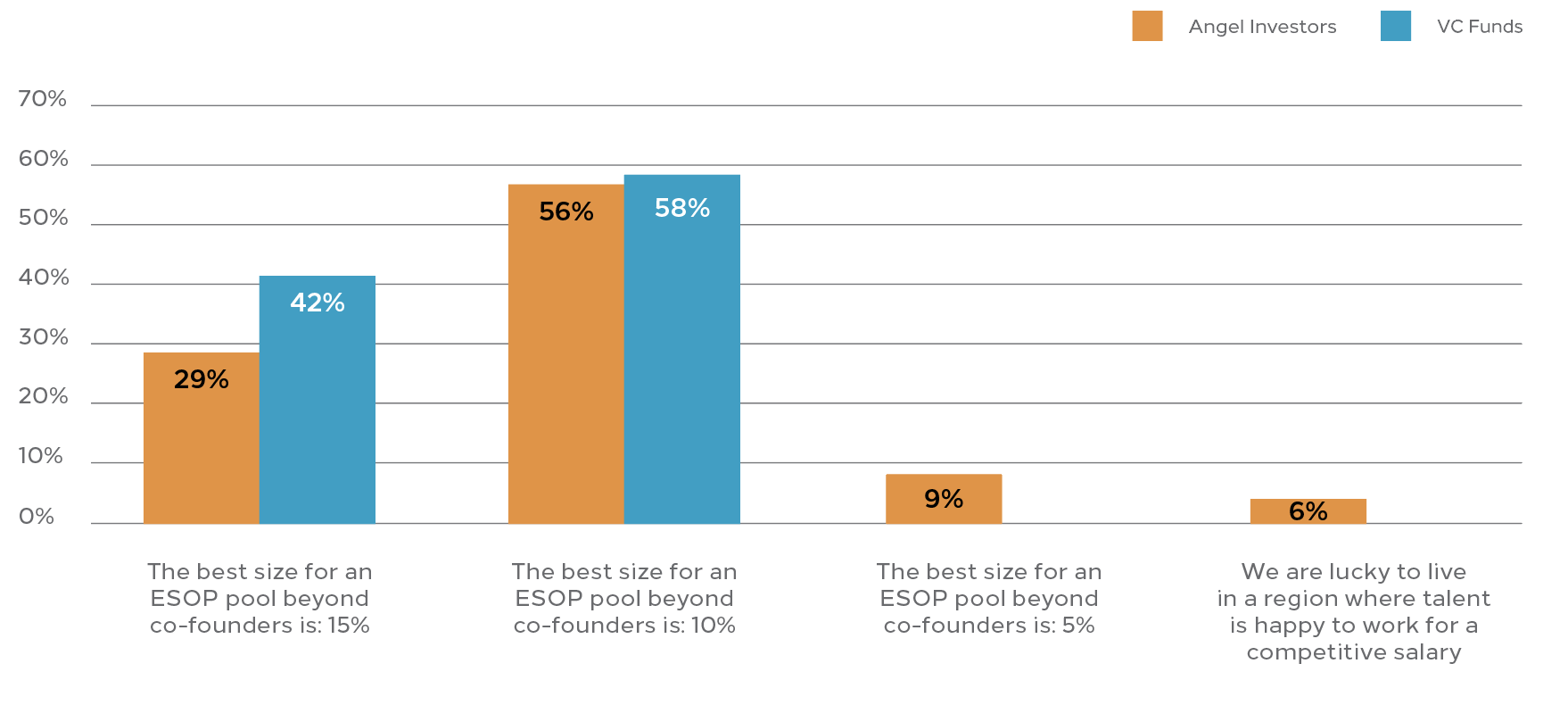

Another crucial consideration when developing a start-up is incentivizing employees. ESOPs are a strong, if not the best, tool to attract and retain top talent. We asked investor about their views:

ESOP

As expected, all investors find this crucial. There seems to be a market standard around 10% of fully-diluted equity reserved for incentivizing talent. A few years ago, the market standard was completely different and high salaries without equity were commonplace. With the growth of the ecosystem, founders came to realize that retaining top employees long-term was one of the most important thing and ESOPs were a way to make them a lasting part of the adventure. Market standard has shifted towards widespread adoption of ESOP. We can note that venture investors seem more inclined to allow for bigger ESOP pools, as they invest a stage where headcount growth is one of the key challenges, and many employees will need to be hired.

Market considerations

Another vertical we explored is the perception of the market by investors.

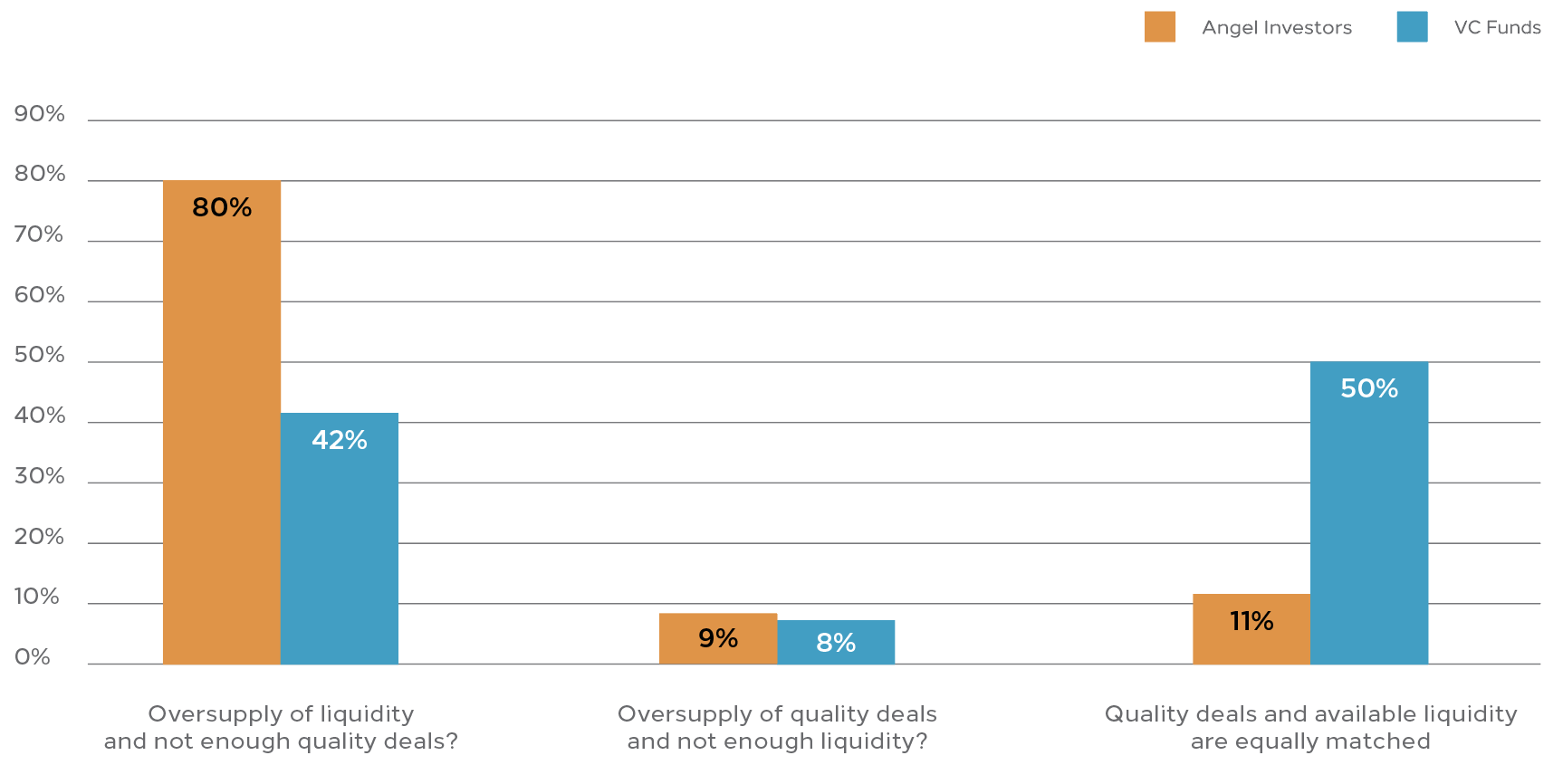

In terms of VC investments in the stage you invest in, the MENA region suffers from:

Angel investors overwhelmingly find that an oversupply of capital is present, while that sentiment is more tempered in venture investors. In our region, the ratio of angel investors to very early-stage companies is far greater than the ratio of venture capital funds to early-stage companies. This results in the fact that on average, angel investors see less deals, and less quality deals, than venture investors.

We must see this response as an opportunity to be seized. By continuing the efforts of growing the entrepreneurial ecosystem and creating support structures such as incubators, accelerators, and networks, we will allow more people to become founders. By lessening the risk of founding a company, potential founders that are on the hedge will accept the risk and launch their start-up. The capital available today will create the unicorns of tomorrow. Our region had a mismatch between capital and opportunities, and many governments and private entities are working at bridging that gap, and strengthening the region’s ecosystem.

The improvements of the ecosystem are met with enthusiasm from beyond our region:

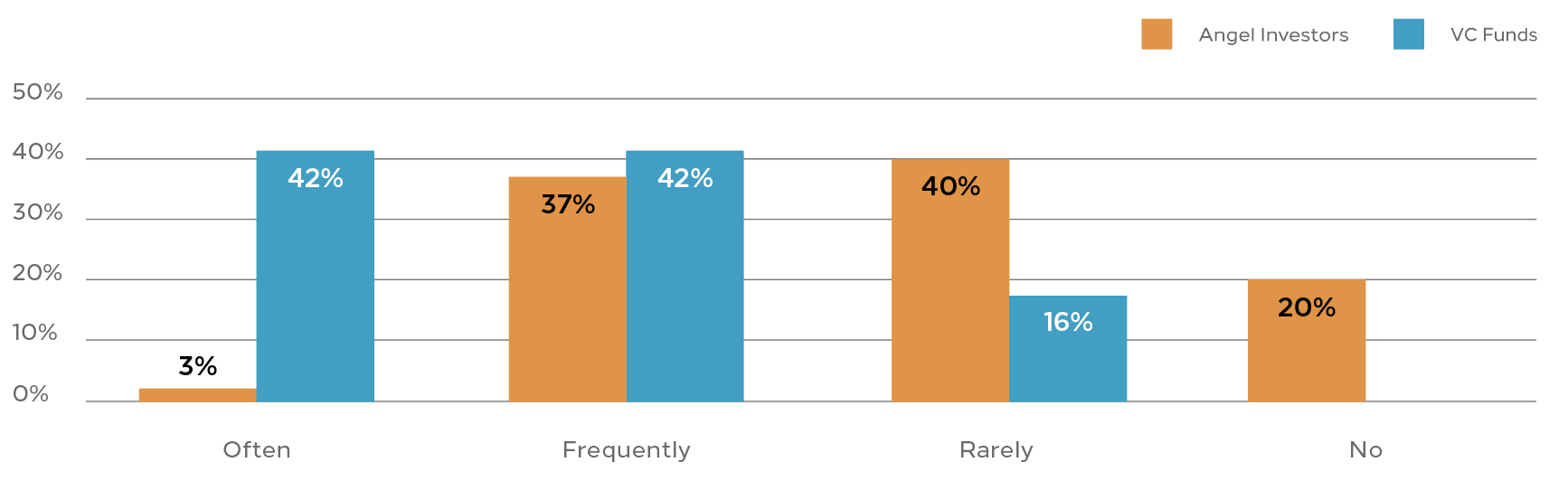

Do you work with VCs outside the region on deals?

This shows a strong interest and proves that the market believes in the MENA region. However, it is important to note that start-ups used to seek funding from international funds as there was no regional capital available for later stage start-ups. In the past couple years, this has drastically changed and the appetite for international investors is not driven by the lack of regional options anymore but rather by the heightened ambitions of MENA start-ups that want to penetrate markets beyond the region.

Those ambitions must be seen in light of the following finding:

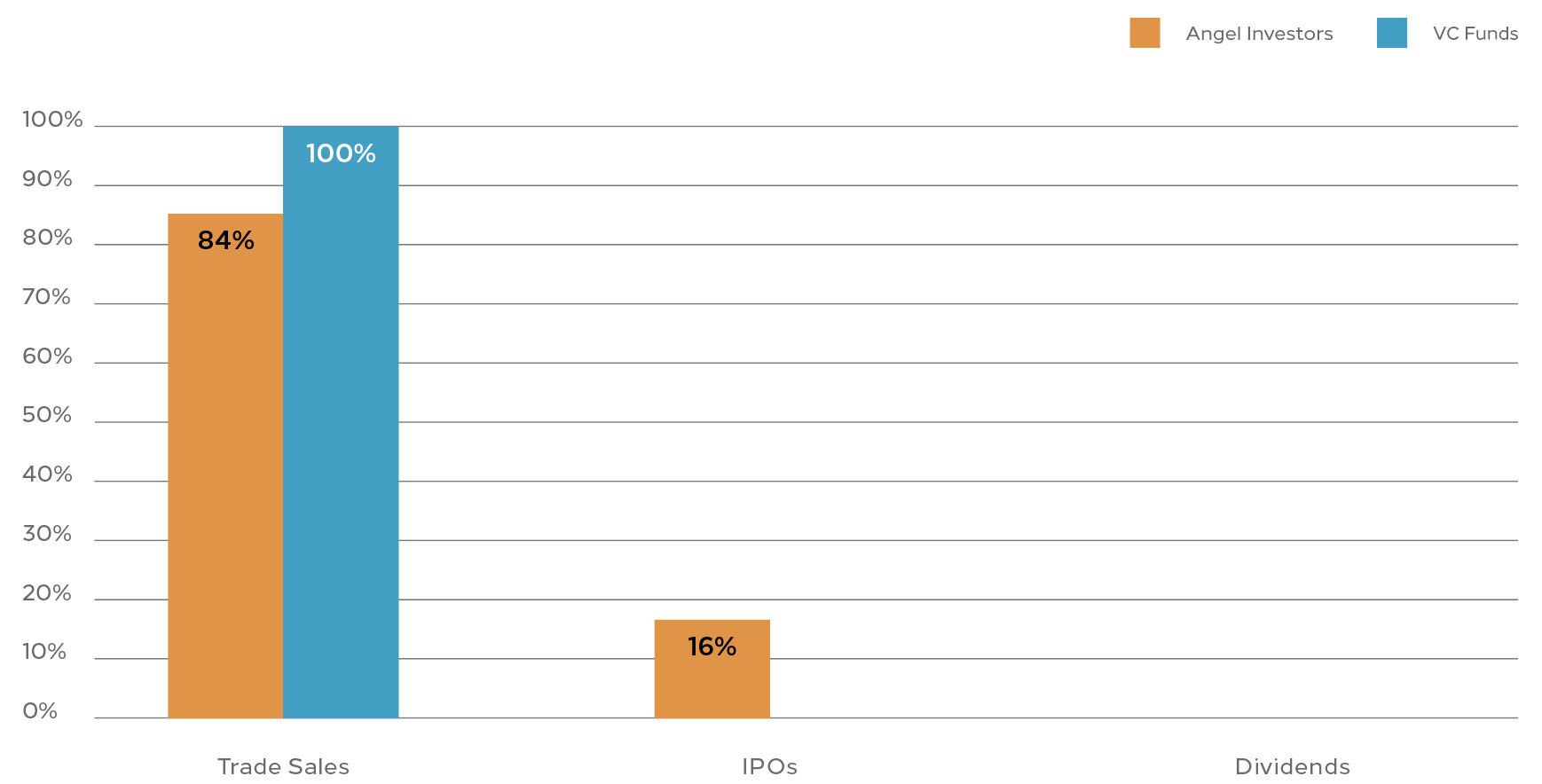

What are your plans for exits?

All investors believe that trade sales are the main, if not the only, exit option. This echoes what the ecosystem trend has been, with all major successful exits being acquisition by tech giants. Major international companies will acquire MENA start-ups and use their specific market knowledge and established dominance. Careem and Souq are the prime examples of this trend.

For now, there is little chance that a MENA start-up will establish itself as the major global player in its vertical. However, there is a good chance that a striving start-up will become the regional operator of a global player. Venture investors’ and angels’ enthusiasm shows that the market for major exits is there, the only caveat being that this market is thought to be limited to acquisitions.

Focus on venture funds

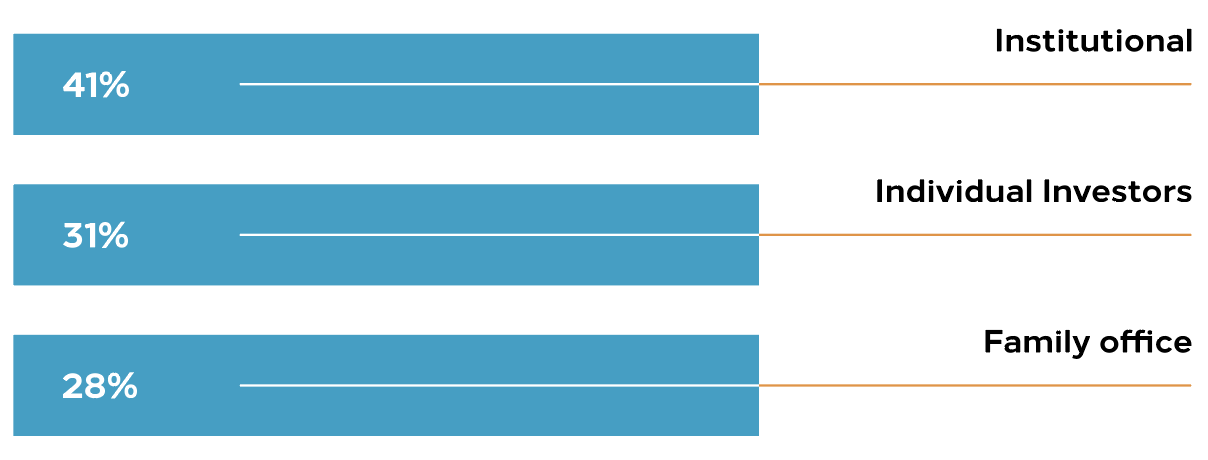

A final point of research was focused on venture funds and their composition:

This finding only reinforced our belief that the asset class is gaining traction across the region. The almost even mix of limited partners shows that venture is now seen as a diversification asset class rather than a gamble for daredevils.

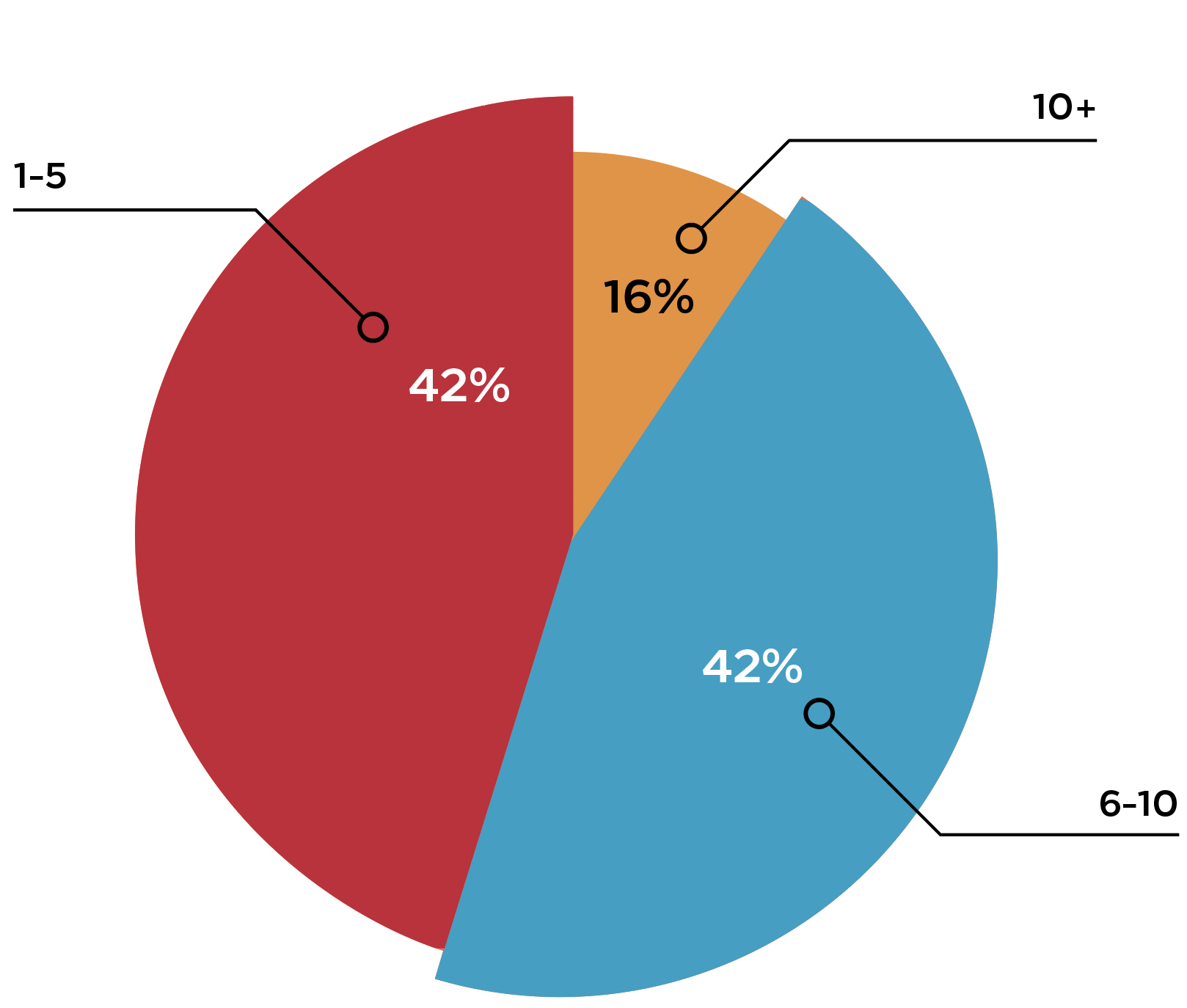

This is further demonstrated by the growing number of funds and their varied approach to investing. Our last finding was that venture funds in the region had many different operational models, ranging from boutiques to more institutional entities, as shown by the varied headcount in different funds. This allows start-ups to find in a fund not only an investor, but also a partner that matches their expectations, no matter what they are:

How big is your team (excluding advisors, consultants)?

Stay updated

To learn more about our services and get the latest legal insights from across the Middle East and North Africa region, click on the link below.