- Arbitration

- Banking & Finance

- Capital Markets

- Commercial

- Competition

- Construction & Infrastructure

- Corporate / Mergers & Acquisitions

- Corporate Services

- Corporate Structuring

- Digital & Data

- Dispute Resolution

- Employment & Incentives

- Family Business & Private Wealth

- Innovation, Patents & Industrial Property (3IP)

- Insurance

Find a Lawyer

Book an appointment with us, or search the directory to find the right lawyer for you directly through the app.

Find out more

Level Up: Unlocking Financial Potential In The Middle East

Welcome to this edition of Law Update, where we focus on the ever-evolving landscape of financial services regulation across the region. As the financial markets in the region continue to grow and diversify, this issue provides timely insights into the key regulatory developments shaping banking, investment, insolvency, and emerging technologies.

2025 is set to be a game-changer for the MENA region, with legal and regulatory shifts from 2024 continuing to reshape its economic landscape. Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Egypt, Iraq, Qatar, and Bahrain are all implementing groundbreaking reforms in sustainable financing, investment laws, labor regulations, and dispute resolution. As the region positions itself for deeper global integration, businesses must adapt to a rapidly evolving legal environment.

Our Eyes on 2025 publication provides essential insights and practical guidance on the key legal updates shaping the year ahead—equipping you with the knowledge to stay ahead in this dynamic market.

The leading law firm in the Middle East & North Africa region.

A complete spectrum of legal services across jurisdictions in the Middle East & North Africa.

-

Practices

- All Practices

- Banking & Finance

- Capital Markets

- Commercial

- Competition

- Construction & Infrastructure

- Corporate / Mergers & Acquisitions

- Corporate Services

- Corporate Structuring

-

Sectors

-

Country Groups

-

Client Solutions

Today's news and tomorrow's trends from around the region.

17 offices across the Middle East & North Africa.

Our Services

Back

Back

-

Practices

- All Practices

- Banking & Finance

- Capital Markets

- Commercial

- Competition

- Construction & Infrastructure

- Corporate / Mergers & Acquisitions

- Corporate Services

- Corporate Structuring

- Digital & Data

- Dispute Resolution

- Employment & Incentives

- Family Business & Private Wealth

- Innovation, Patents & Industrial Property (3IP)

- Insurance

- Intellectual Property

- Legislative Drafting

- Private Client Services

- Private Equity

- Private Notary

- Projects

- Real Estate

- Regulatory

- Tax

- Turnaround, Restructuring & Insolvency

- White Collar Crime & Investigations

-

Sectors

-

Country Groups

-

Client Solutions

- Law Firm

- /

- Insights

- /

- Law Update

- /

- June 2020

- /

- Putting the Pieces Together: Anti-Corruption and Competition Defence Mechanisms

Putting the Pieces Together: Anti-Corruption and Competition Defence Mechanisms

Ibtissem Lassoued - Partner, Co-Head of White Collar Crime & Investigations - White Collar Crime & Investigations / Family Business

Mariam Sabet - Partner - Competition / Intellectual Property

The old adage of crises providing useful opportunities for reform posits a bright outlook for dark times, but businesses trying to sustain their livelihood through difficult periods often face more confronting circumstances. Irrespective of the source or scale of a crisis, all such events have the potential to cause significant disruption to businesses that are attempting to operate within the affected vicinity. This can be through interruptions to the supply chain, diminution in consumer demand, collapse of operations infrastructure, or severance from consumer markets. Whether these obstacles occur suddenly or are looming on the horizon behind an impending catastrophe, businesses are faced with serious cash flow problems, and in some cases existential threats to their survival.

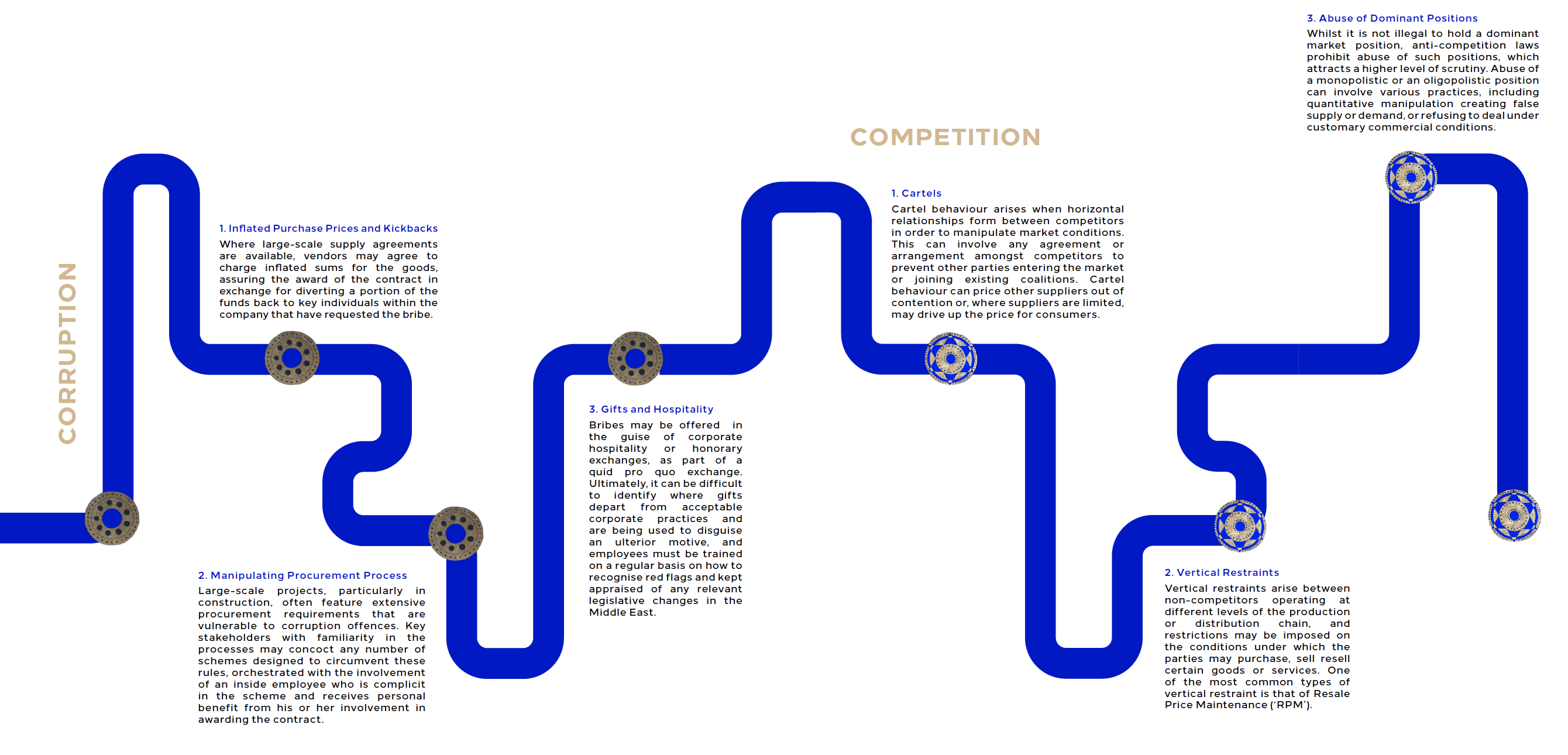

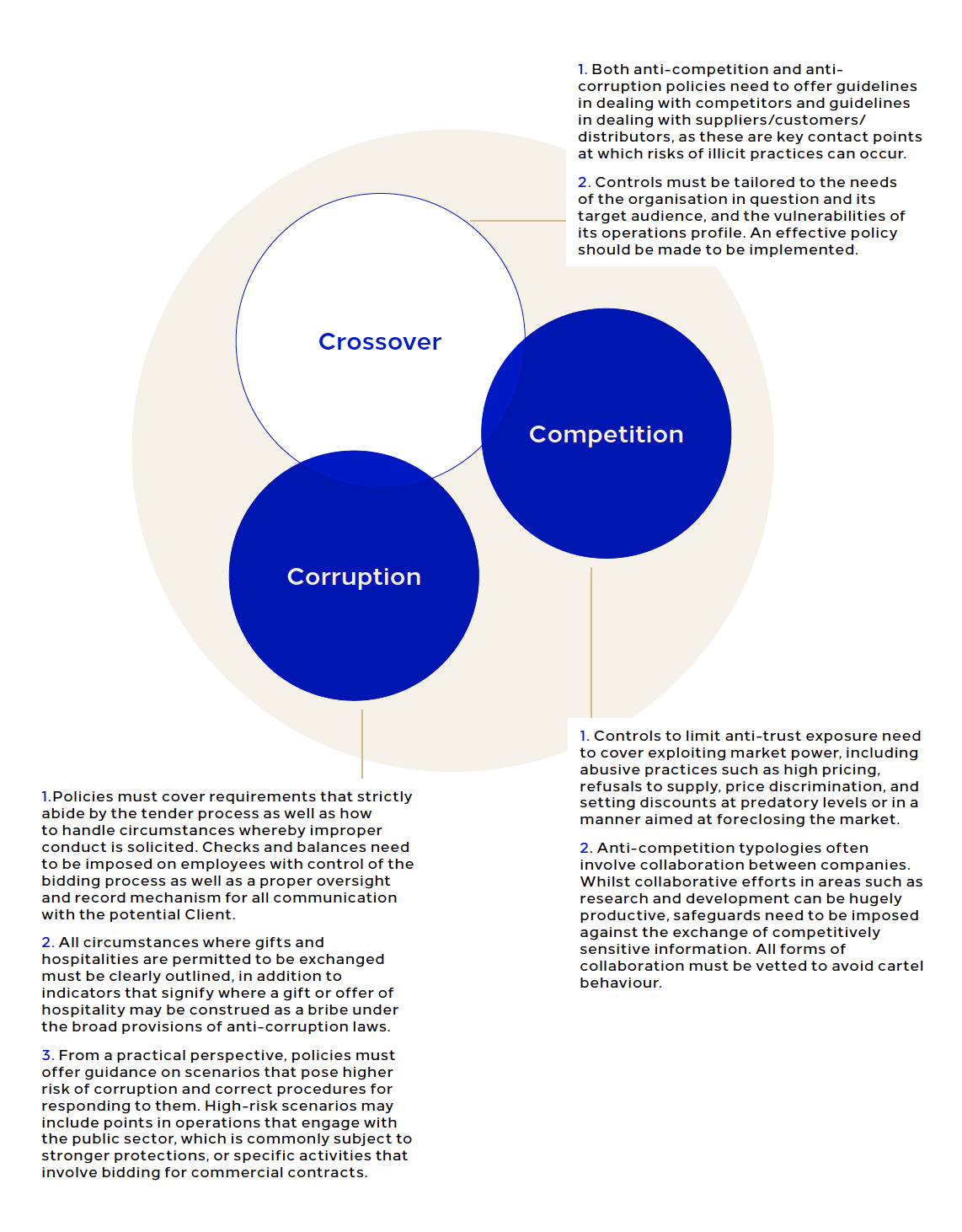

Companies that are affected by such circumstances are put under exceptional pressure to find ways to sustain their business and, in some instances, this can be sufficient to persuade them to compromise their values, attempting to gain undue advantage over market competitors by crossing the ethical line. The nefarious methods available to companies that vie for advantageous position are multifarious, with schemes that can include both anti-competitive and corrupt practices. Despite the divided nomenclature, both anti-corruption and anti-competition risks arise in similar circumstances and often plans involving one will contain elements of the other. Procurement processes in particular, for example, exhibit significant linkages between anti-competitive practices and corruption methodologies, whereby bids can gain more favourable responses by way of paying bribes or by colluding with other companies for example.

The laws that govern these two separate types of wrongdoing are divided: UAE Federal Law No. 4 of 2012 sets out the initial competition protections with its implementing regulations passed in 2014 and further Cabinet Resolutions passed in 2016 with respect to market share thresholds; in Saudi Arabia, more recent legislation was passed in September 2019. Anti-corruption provisions, meanwhile are contained in widespread laws in both the UAE and Saudi Arabia. In practical terms, however, there is significant overlap in the defences that are deployed against them. The primary measure that is used by companies against such practices, which carry significant legal implications under the law, is internal compliance programmes that prohibit certain types of behaviour that would invoke liability for anti-competitive practices or corruption offences.

Internal policies need to be robust, but they also need to be user friendly and understood by employees in order for implementation to be effective. Controls that address the relevant points under the law in Middle Eastern countries but which fail to take into account the risks and scenarios that arise for employees on a daily basis are rarely effective, as they fail to demonstrate to employees how they should be applied to routine occurrences in the course of operations. For example, if the internal code of ethics of a UAE company prohibits employees from accepting any improper benefit (in compliance with Law No. 3 of 1987 (as amended) promulgating the Penal Code) yet it does not offer any guidance to employees on how to assess and/or identify gifts that may constitute a bribe (and those that do not), the effectiveness of the policy will be fatally undermined. Likewise, internal competition policies may demonstrate a general commitment to avoiding behaviours that would exploit market power, but this is only fractured protection if the policy does not also identify and explain how certain commercial decisions, such as pricing and discount, may trigger accusations of abusing a dominant position.

The specific competition and corruption risks that arise in the course of business vary between sectors and countries, shaped to the wider context of the regulatory environment, business and compliance culture and economic conditions. As such, it is important that policies are tailored to anticipate the specific risks and scenarios they are designed to prevent, and that employees are properly trained on how to understand and implement them. In the event of crisis, internal controls are put under intense stress as external conditions ramp up the pressure and companies are driven to look for new ways to navigate the market. Anti-corruption and competition policies are interrelated pieces of a company’s defence, and companies need to make sure they are locked in place and functioning effectively to keep themselves running, even during a time of crisis.

Common Mechanisms Used to Gain Advantage

Assembling Effective Defences

Time is Precious

Acrylic, gold metal leaf on canvas

170 x 150 cm

Curated by Rebia Naim @EmergingScene

Stay updated

To learn more about our services and get the latest legal insights from across the Middle East and North Africa region, click on the link below.