The Economics of a Venture Capital Deal

Abdullah Mutawi - Partner, Head of Corporate Commercial - Corporate / Mergers and Acquisitions / Commercial / Private Equity / Digital & Data / Turnaround, Restructuring and Insolvency / Venture Capital and Emerging Companies

Kareem Zureikat - Senior Associate - Corporate / Mergers and Acquisitions / Commercial / Venture Capital and Emerging Companies

Haya Al-Barqawi

“Our team has a deep understanding of the commercial dynamics of venture-backed businesses across multiple verticals and business models. The breadth and depth of our experience enables us frequently to suggest legal terms and solutions that are informed by that knowledge and the understanding that not all tech companies are equal when it comes to the commercial dynamics of the go-to-market and customer acquisition strategies, and the rate at which revenue generation can catch up with demands on capital and burn rates. On more than one occasion, we have advised a company to stress-test its financing strategy based on what we expect the company to need in further cash and, when such need is likely to occur.”

Investors, whether in connection with a buyout, a late-stage investment, or an early-stage investment, are looking to capitalize on their investments. In a venture capital context, investments in early or growth stage start-ups are considered “high-risk-high-reward”, and investors look for more robust mechanisms to ensure that the value of their investment is protected. Liquidation preferences and anti-dilution protection are two of several venture-capital-specific provisions that provide a measure of comfort to investors.

Liquidation Preferences

As valuations balloon with each equity funding round, investors in each new round want some level of certainty that they will receive a return on their investment on a sale of their shares, and in a venture capital context, investors tend to take on larger risks when investing in start-ups that do not have either a strong track record or positive earnings. A liquidation preference therefore offers investors a tool to ensure they receive their investment back in preference and priority to other shareholders in certain specific cases.

Liquidation preferences are triggered on the occurrence of a “liquidity event”, which typically includes: (1) a sale of a majority of the voting rights of the start-up; (2) a sale of majority of the assets of the start-up; (3) a winding up; or (4) an IPO.

Three main limbs to understanding liquidation preferences are:

- Participation;

- Seniority; and

- Multiple.

Participation

Participating Liquidation Preference: In a participating liquidation preference, the investor gets a complete return of their capital investment first and in priority to all other shareholders, and then has the right to “participate” in the remaining proceeds distributed to all shareholders on a pro rata basis with the remaining shareholders.

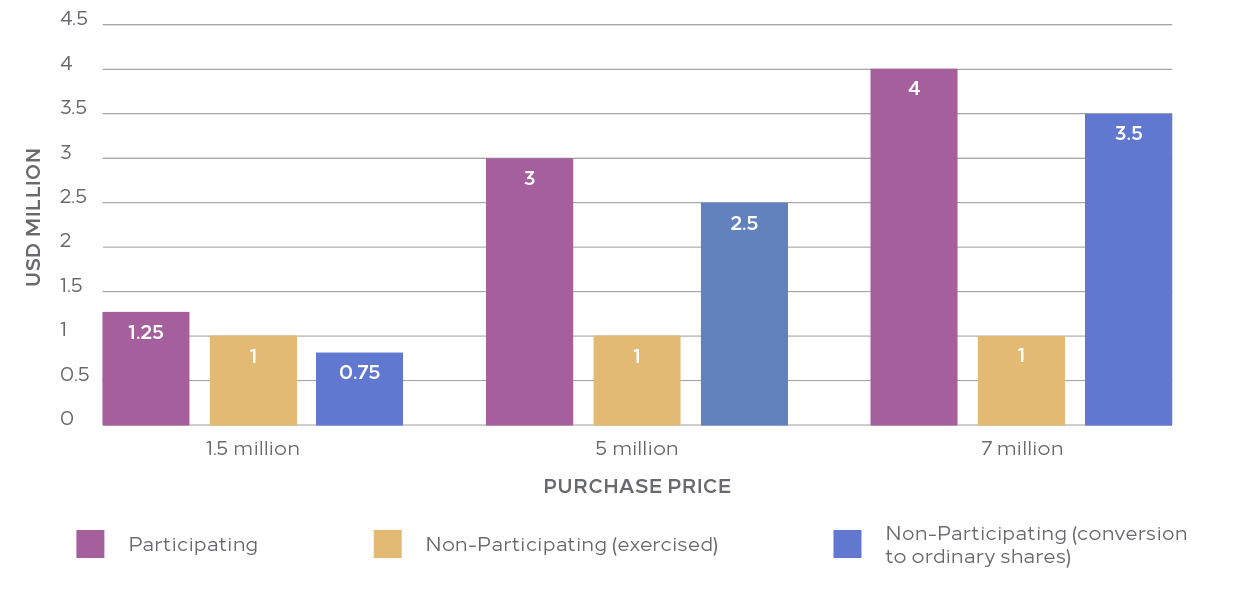

By way of example, assume an investor made an investment of USD 1,000,000 in consideration for 100,000 Preferred Shares, for a resulting ownership of 50% of the start-up’s share capital. The terms of the investment include a liquidation preference equal to the full value of the USD 1,000,000 investment. The start-up does not perform as expected, and one year later, 100% of the start-up’s shares are sold to a private equity investor at a total valuation of USD 1,500,000. Given that the investor has a liquidation preference in respect of the full value of its investment, the investor will receive USD 1,000,000 from the buyout, with the remaining USD 500,000 distributed to all shareholders pro rata. Had no such liquidation preference been included, the investor would have received USD 750,000, representing its 50% share of the total purchase price. But given that the investor has participation rights, the investor would first receive its USD 1,000,000, and would then be able to participate, on a pro rata basis, with the remaining shareholders in the remaining USD 500,000, and would therefore receive USD 1,250,000, which is its USD 1,000,000 investment, plus its pro rata share (namely 50%) of the remaining USD 500,000, which is an amount equal to USD 250,000.

Non-Participating Liquidation Preference: Unlike a participating liquidation preference, a non-participating liquidation preference gives the investor the choice of whether to be paid back its entire capital investment or alternatively share the proceeds of the liquidity event on a pro rata basis with all shareholders. The investor will choose the option which yields the largest returns. This is a more balanced liquidation preference as the investor does not receive two separate distributions as it would have had it held participation rights.

If we use the example above where an investor has made an investment of USD 1,000,000 for 50% of a start-up’s share capital, and the start-up’s shares are once again sold at a total valuation of USD 1,500,000, the investor would have to make a choice between two possible options; the investor could either exercise the liquidation preference and receive a guaranteed USD 1,000,000 back, or alternatively, can choose to convert its preferred shares to ordinary shares for USD 750,000 (i.e. 50% of 1.5 million). The choice here seems obvious, and the investor would most likely opt for the USD 1,000,000. However, should the company sell for a value higher than was anticipated, the investor will choose to receive its pro rata portion of the consideration.

Participating Liquidation Preference

Seniority

It is particularly important for entrepreneurs and venture capitalists to understand seniority structures when making an investment in order to determine where and when they will get their payout. While originally, pari passu structures were more common, standard seniority structures are gaining popularity for several years now.

Standard Seniority: As a general approach to venture capital funding rounds, new equity-round investors are offered preferred shares which carry preferential economic and voting rights. Therefore, liquidation preferences can be “stacked”, and payouts are in order form latest round to earliest round. This is the standard “last in, first out” approach, and each new funding round investor would receive its payout prior to the investors of the preceding funding round. The obvious risk for founders and early stage investors is that they could be left with little (to nothing at all) if the proceeds from the liquidity event are insufficient and the waterfall dries up due to payments of more senior liquidation preferences before more junior preference holders can realize a return.

Pari Passu Seniority: A pari passu liquidation preference gives all investors holding preferred shares equal seniority status. This means that all investors would share in at least some part of the proceeds and no one is left with nothing.

Tiered Seniority: This liquidation preference right is a hybrid of standard and pari passu seniority, where investors from different funding rounds are grouped into distinct seniority levels or “tiers”. Each tier of investors would then be treated as a separate class in terms of liquidation seniority, and the standard seniority approach would apply to each tier of investors. Then, within each tier, investors of that tier are paid in a pari passu format.

Return Multiples

A 1x multiple guarantees that the investor gets 100% of their money back. While the market standard approach to a liquidation preference is to grant the investor the right to receive all of its invested capital (which is venture capital lingo is a “1x liquidation preference”), investors may, in certain circumstances, request a multiple of their capital invested. Therefore, an investor may request 2x or 3x its invested capital to be paid on the occurrence of a liquidity event. While 2x or 3x multiples may be acceptable in certain rare scenarios, for example where a start-up may be willing to offer such return multiples in an insolvency rescue funding round, the market standard approach in the Middle East is a 1x liquidation preference.

Anti-Dilution Protection

Anti-dilution protection operates to preserve the economic value and not the ownership percentage of an investor’s investment. It is therefore, in its simplest form, a mechanism that grants investors additional shares to compensate them for the diminution of the start-up’s valuation in the future.

Anti-dilution provisions are typically included in a shareholders’ agreement entered into between the shareholders and the start-up. Venture capital transactions in the United States do not typically use a shareholders’ agreement, and the anti-dilution provisions are included in the amended and restated charter.

To illustrate potential investment risks that may arise, and how an anti-dilution right can protect the value of an investment, let’s take the following example:

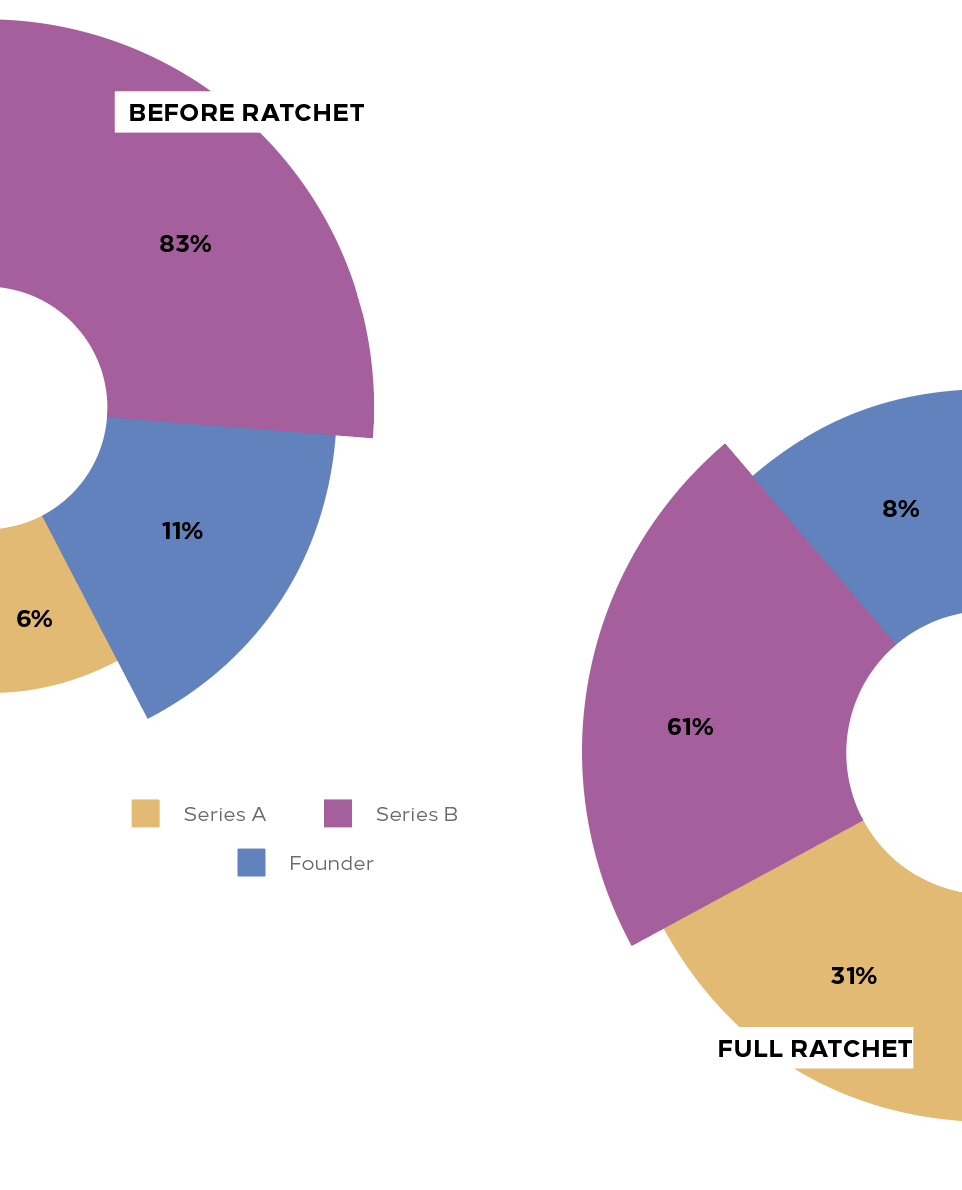

A company has a total of 1,000,000 shares in issue, all of which are issued to its founder prior to its Series A funding round. The start-up has found one investor for its Series A funding round, and the start-up and investor have agreed to an investment at a pre-money valuation of the start-up equal to USD 10,000,000. The investor agrees to invest USD 5,000,000 in the Series A funding round, at price per share equal to USD 10 (the 10,000,000 valuation divided by the 1,000,000 shares in issue). The company’s issued share capital after the Series A round is 1,500,000, which is comprised of the founder’s original 1,000,000 shares plus the new 500,000 Series A shares issued to the investor (calculated by dividing the investment amount (USD 5,000,000) by the price per share USD 10), and therefore the founder owns 66.67% of the company and the Series A investor owns 33.3%.

Assume, that the Series B funding round valuation was less than the Series A valuation (i.e. the value of the start-up after the closing of the Series A funding round diminished). This is what is called a ‘Down Round’ in a venture capital context. What would happen then? For illustrative purposes, assume (in a rather extreme case) that the start-up has not done well and the Series B funding round occurs at a pre-money valuation of USD 2,000,000, which means the price per share for the Series B investor is USD 1.33. Assume also that the Series B investor invests USD 10,000,000 as part of the Series B funding round, the Series B investor would receive almost 7,518,796 new Series B preferred shares.

In this case, the Series A investor’s overall ownership and value position has deteriorated significantly; its ownership has been diluted to 5.5%, and its 500,000 shares that were once worth USD 10 per share are now worth USD 1.33 per share!

Given the loss of return due to the devaluation of the start-up, anti-dilution protections kick-in during a Down Round to adjust the overall value of the Series A investor’s position by allocating more shares to the Series A investor. So how does this happen?

If a Down Round closes, the anti-dilution provisions under the relevant documents may provide that the start-up would issue to the Series A investor ‘bonus shares’ to compensate for the diminution in the Series A investor’s investment. These shares would be issued for no consideration, or, if that is not permissible under applicable laws, at par value.

An alternative and more common mechanism is to adjust the “Conversion Price” for the Series A investor. Given that investors typically receive preferred shares when investing in a start-up, the funding round documents provide for a mechanism for conversion of the preferred shares into common shares, for example, on an initial public offering. The Conversion Price usually starts as the price per share at which an investor has subscribed for its shares and this would then be adjusted in the event of a Down Round. Therefore, using our example above, the initial conversion price for the Series A investor is USD 10. If, however, the start-up closes a Down Round, the Conversion Price will be adjusted downwards such that, upon conversion of preferred shares into common shares, the holder of preferred shares would receive more ordinary shares for its preferred shares (i.e. the conversion is no longer a 1:1 for the conversion of a preferred share to an ordinary share). This is because an investment of USD 5,000,000 at a price per share lower than USD 10 results in more shares being issued to the investor.

Whether the agreements provide for the issue of bonus shares or an adjustment to the Conversion Price, anti-dilution provisions are inherently tied to the value of the shares.

So how do we calculate the number of ‘bonus shares’ or the adjusted Conversion Price based on the price per share paid by the investor?

There are two formulas; a weighted average formula and a full ratchet formula. The full ratchet formula is a rather draconian approach to anti-dilution, and the venture capital ecosystem has moved further away from full ratchet anti-dilution protection, although it may still appear or otherwise be justified in certain specific instances, for example, when an investor is investing in a distressed start-up and seeks additional protections.

“While commonly misinterpreted as a right of first refusal on capital raises (i.e. the right to maintain the same ownership percentage in a company on new dilutive issues of shares) anti-dilution protection operates to preserve the economic value and not the ownership percentage of an investor’s investment. It is therefore, in its simplest form, a mechanism that grants investors additional shares to compensate them for the diminution of the start-up’s valuation in the future.”

The full ratchet formula is straight forward; it replaces the price per share at which an investor has invested (using our example, a price per share of USD 10 for the Series A investor) with the price per share paid by investors in the next funding Down Round (using our example, a price per share of USD 1.33 paid by the Series B investor). Therefore, the Series A investor would receive such number of shares had the Series A investor subscribed for shares at a price of USD 1.33 (i.e. its original investment of USD 5,000,000 divided by USD 1.33, which gives the Series A investor a total of 3,759,398 shares). That’s more than 3,200,000 “bonus shares” issued to the Series A investor.

The weighted average formula is slightly more complicated, as the formula does not simply substitute the original price per share (i.e. USD 10 for our Series A investor) with the new price per share (i.e. USD 1.33), but rather assesses the weighted average effect of the amount of money raised during, and the share price for, the Series A funding round, together with the amount of money raised under, and the share price for, the Series B Down Round, on the overall value and capitalisation of the start-up.

There are two weighted average formulas; a broad-based formula, and a narrow based formula. A narrow-based formula only takes into account the issued preferred shares of the start-up, whereas the broad-based formula takes into account the fully diluted capitalisation of the start-up (i.e. all issued shares, including common and preferred shares). Narrow-based formulas are investor-friendly, as they result in a more significant reduction in the Conversion Price on a Down Round when compared to the broad-based formula.

The issue of shares pursuant to anti-dilution clauses comes at the expense of someone else: the founder or other holders of other shares that do not carry anti-dilution rights or who’s anti-dilution rights are not triggered by the Down Round. Therefore, one perspective is that anti-dilution penalises the founder for the start-up’s lack of success, although investors would argue that this is fair and reasonable given that it is the founder(s) that drive the day-to-day business.

Liquidation rights and anti-dilution rights can carry significant implications on the investor and the founders, so it is vital that legal and financial advice is sought prior to agreeing to confer any such rights under the terms of each equity funding transaction.

Stay updated

To learn more about our services and get the latest legal insights from across the Middle East and North Africa region, click on the link below.